As the Picture Darkens

Nowhere does the new seem so visible as where something is going to 'rack and ruin': the ruins which themselves contain the basis for the new.

Jean Gebser

On the morning of January 6th, the anniversary of the 2021 insurrection, in the wake of the abduction of Venezuela's President Maduro, the New York Times reported that President's Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller, told CNN host Jake Tapper that Greenland belonged to the US: "Nobody's going to fight the United States' military over the future of Greenland...We live in a world, in the real world, Jake, that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power. These are the iron laws of the world since the beginning of time.”

Tyrants and wannabes have uttered similar sentiments before without realizing they were preparing the ground for their own demise. Because such language elicits echoes of other banal yet pointed phrases: "He who lives by the sword...." Genghis Khan put it this way: "Might makes right." But he was a little wiser (and more powerful, as well as more tolerant) than Miller, as he's also purported to have observed, "Conquering the world on horseback is easy. It's dismounting and governing it that's hard."

When you dismount, you get a real world look at the damage you have done—not just to "the real world”, but to other living beings, as dimensional and infinite as you, and to yourself. Even if you never directly confront the harm you've caused, never face the families you've shattered through brutal deportations, never see the grieving wives and children of the soldiers you've murdered in extracting the dictator, brutalizing others, you inevitably brutalize yourself.

It's Caesar's world Miller describes: ruthless, feckless, treacherous, and devoid of love. (Worth remembering, too, how Caesar’s story ends.) Of course, Caesar’s kingdom has traditionally been juxtaposed against another, subtler reality often referred to as the moral realm (also known as God’s kingdom). It’s a space anyone staking a claim to the Judeo-Christian tradition had best take seriously. The exploration of that territory, whose rules and principles are to the so-called “iron laws” of the world as Quantum theory is to Newtonian physics, precedes Jesus, of course. Every system of ethics ever evolved, from Confucianism to Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics to the democratic socialism of Mills to Rawls theory of “justice as fairness,” has arisen from an attempt to discover what to do when you finally get off that high horse—for get off you must. Indeed, the language for this has been codified inside the framework of most of the world's religions. There is, for example, Rabbi Hillel's golden rule: "What is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow. This is the whole Torah; the rest is commentary."

And then there is the New Testament.

Stephen Miller may appear in his own mind a very powerful man. He may claim to be the great defender of the "Judeo-Christian West," and insist that "Christianity is embedded in the very soul of our nation." But let me invite Jesus Christ and his mouthful of Beatitudes into the room: "Blessed are the merciful, for they will be shown mercy....Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called the children of God." What continues to make the New Testament such a radical document is Christ's message of non-violence—which, as we know, does not translate into passivity but rather encourages active non-violent resistance.

On the topic of resistance, this past December I was invited to say a few words at the annual Christmas luncheon of the Saturday Club. It was an honor I accepted not without hesitation. The Saturday Club—the only club to which I've ever belonged—is a storied Boston institution. Informally launched in 1855 by Ralph Waldo Emerson, Horatio Woodman, and Samuel Gray Ward as a place for members to discuss current ideas in science, the arts, history and politics over monthly dinners (later shifting to lunches), initially at Albion House and later at Boston's Parker House Hotel, the club’s early members included Longfellow, Hawthorne, Louis Agassiz and Oliver Wendell Holmes. At one meeting Charles Dickens read from A Christmas Carol; at another, Longfellow floated an early draft of "Paul Revere's Ride."

Today I rather think of it as an extension of the Harvard Club, as so many of its members are affiliated with that university, and I feel myself a bit of an outlier representing the State university. Nevertheless, I've appreciated the opportunity to listen to so many influential voices, from university presidents to former Supreme Court justices, in a more intimate (if not exactly informal) setting, than when I've heard them on television.

The last time I'd been invited to address this august body was in 2017, when my assignment was to speak on the topic of hope. I confess that had been a challenge. But this year's topic, proposed by the Club's president, lutenist, guitarist and early music scholar Victor Coelho, was defiance. I could not imagine a better, more piquant word for this season's homily. Defiance. The very sound flickers with fire and radiates resistance. What I propose is that, to paraphrase my old friend Seamus Heaney, hope and defiance actually rhyme, that every principled act of defiance is, in fact, fueled by hope and contains in embryo the quanta of infinite potential.

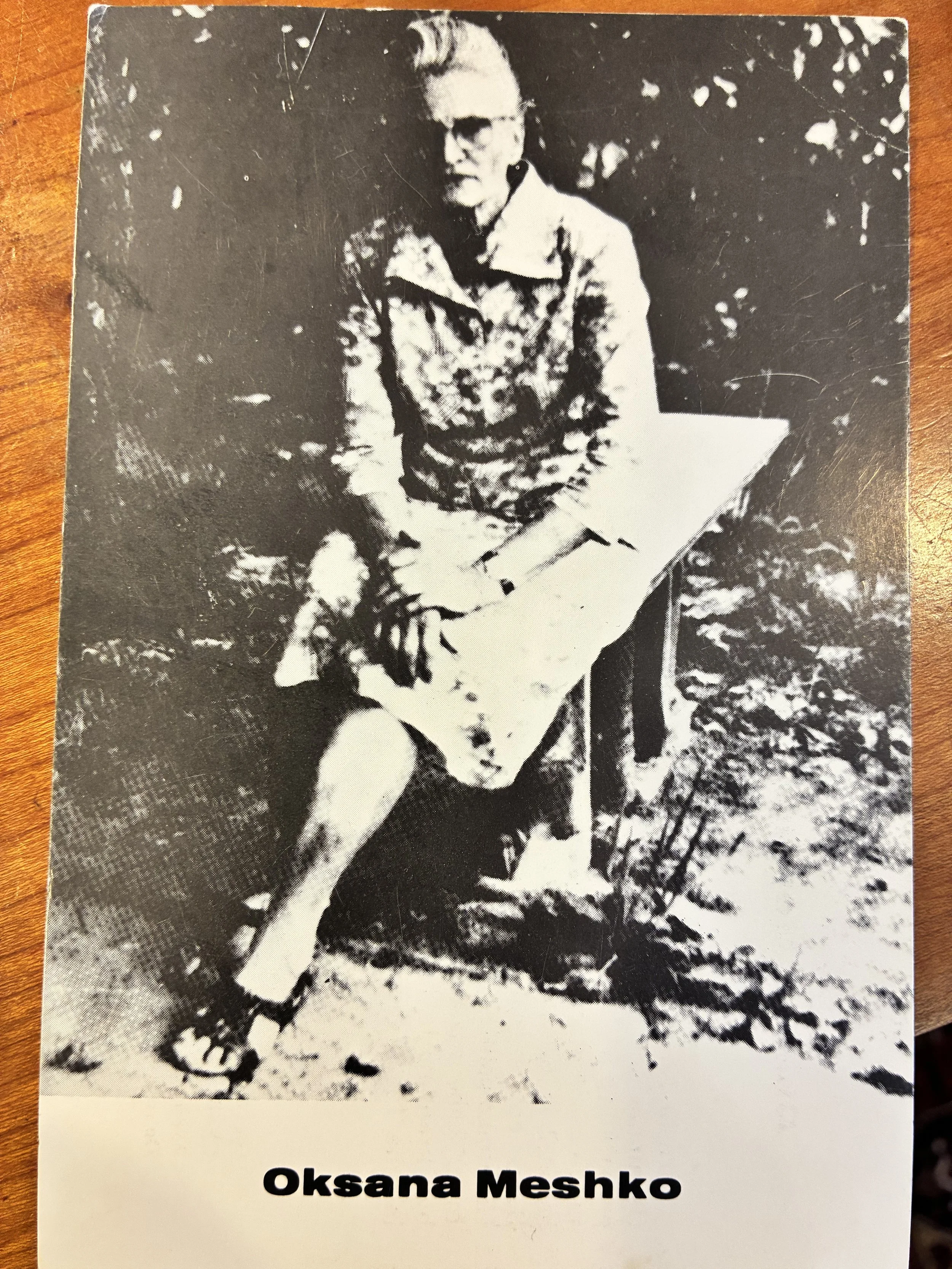

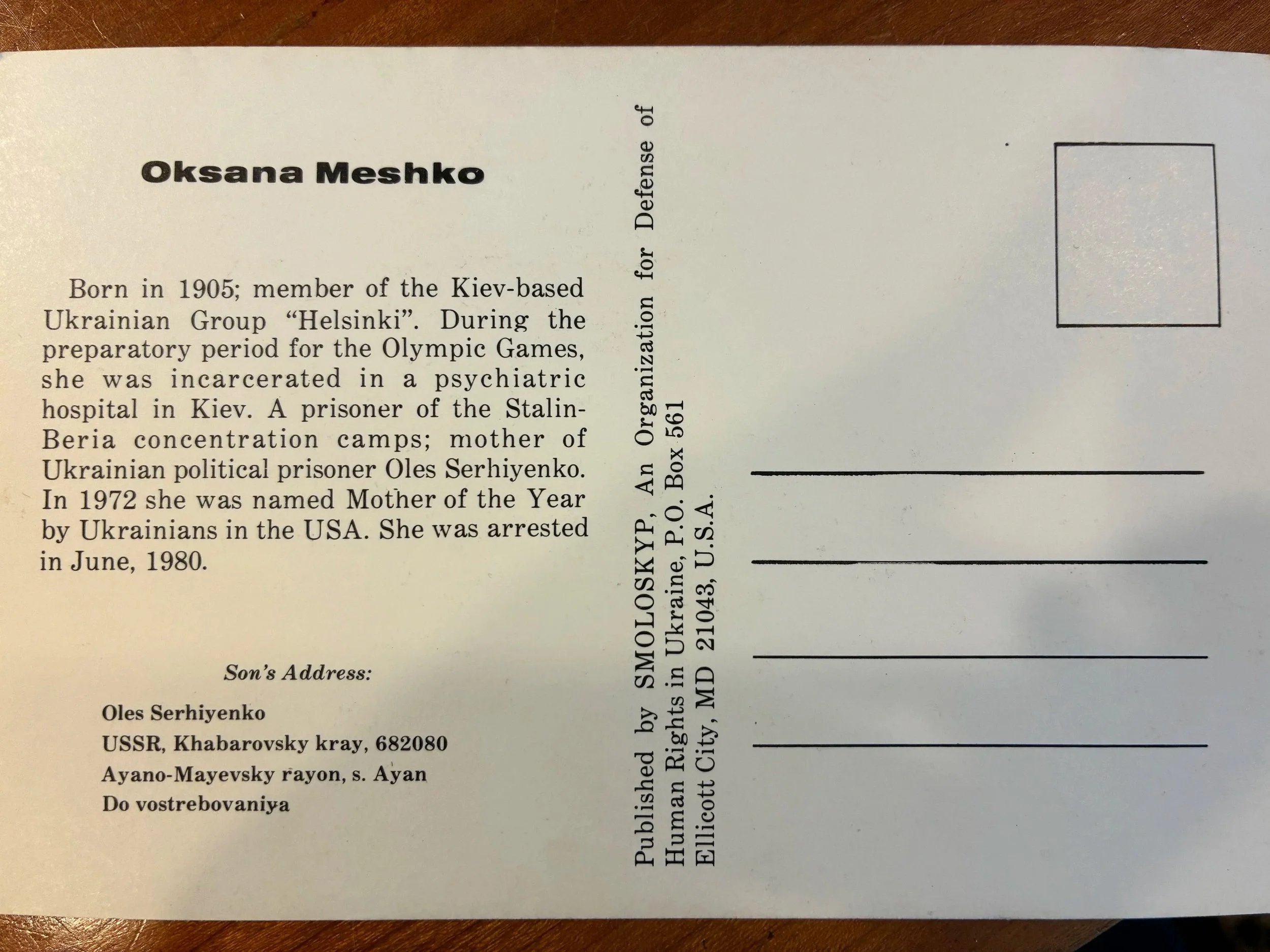

When I was in grade school, I wondered at my classmates gushing over certain rare baseball cards. In my house, we trafficked in Prisoner of Conscience cards. I'm not kidding: these were cards with photographs mainly of the women currently sitting in Soviet gulags deep in the eastern regions of the Russian empire. Photo on the front; stats on the back. Roger Blaine may have had Mickey Mantle, but I had Oksana Meshko. Born in 1905, her father was executed during the Civil War in 1920; one son was killed by a bomb in World War II. In the 60s, she began organizing on behalf of Ukrainian culture, for which another son was kicked out of the University and later arrested. In 1976 she cofounded the Kyiv branch of the Helsinki Group, an international human rights organization. For this she was arrested in 1980 at the age of 75. Eventually released, she even managed to visit the United States. She died in January 1991, 11 months before Ukraine declared independence. The back of her card carries her son's address in the Gulag.

A week before my address, I'd spoken with a cousin in Lviv, a city near the Polish border. The city's comparatively safe and is targeted by drones and missiles only a few times a week, but, my cousin reported, the cemetery has had to open a second branch to accommodate the bodies of the local young women and men killed at the front. Still they remain defiant, unwilling to cede ground in the east even if it means opening a third branch of the cemetery in the west. Because the “territory” is not a barren strip of land–it’s the home of a cousin, a friend from university, a beloved poet.

The first image the word "defiance" evoked for me was of a scene from Casablanca. Against the backdrop of WWII, Rick's Moroccan café, managed by an American refugee (played by Humphrey Bogart), and peopled with refugees escaping the horrors of Europe, is invaded by a gang of uniformed Nazis who decide to entertain themselves by singing a patriotic German song. At that point Victor Laszlo, a leader of the Czech resistance trying to get to the US, leaps up to lead his fellow refugees and their sympathizers in a chorus of Le Marseillaise, which is immediately picked up by Yvonne, the chanteuse performing at the café that evening. The part of Yvonne, incidentally, was played by Madeleine Lebeau, who had in reality fled Paris with her Jewish husband.

The film was co-authored by the Epstein brothers, the father and uncle of my old friend, the late great writer Leslie Epstein—mercifully no relation to that other Epstein whose presence shadows so many of our most prominent local institutions. Indeed, the seemingly irresistible lure of big money on the allegedly intelligent both suggests that we should reconsider our definition of the very word intelligence and puts me in mind of another great scene from world cinema, this time from Godard's masterpiece, Contempt. In it a director, played by the great German refugee director Fritz Lang, himself the Catholic son of a Jewish mother, who is pressured by an American producer (played by the Ukrainian-American actor Jack Palance) quips: "Hollywood did to me with a dollar what Hitler could not do with a gun."

Well, Hollywood has done it again, giving us a 24/7 reality tv show, scripted by a cut-rate de Sade and starring an ensemble cast based at the White House. Each day we see new episodes—children handcuffed, separated from parents, extra-judicial murders, dubious prosecutions, the legalization of bribery, the kidnapping of foreign leaders—all this and more, and it's still early in the show's second season. Never again has been rewritten as Oh why not, so long as it's not me. The Supreme Court approves. The Court of History will not.

Another image that comes to mind draws from a legendary, likely apocryphal, encounter between the great Spanish philosopher, Miguel de Unamuno, rector of the University of Salamanca, and Franco's fascists, who were aiming to occupy it. There are multiple versions of this story, but the one I like best has Unamuno standing at the threshold of the University and declaring to the fascists: "This is the temple of the intellect. I am its high priest and I forbid you to enter."

How we long to hear such sentiments from our institutions' leaders in response to the pressures of politicians, rich trustees and alumni. How we hope for a principled stance, for that future-enabling act of defiance capable of generating that fission-inducing chain reaction which can change everything.

The word defiance also evokes more personal memories of my 87 year-old aunt living outside Washington DC. At the age of seven, she was asked to keep secret from her schoolmates the fact that her father had defied the Occupying Powers, risking his own life as well as the lives of his three children by sheltering his former student, Isidore Scheffler and his wife Esther, from the Nazis who had begun "liquidating" the ghetto. The Schefflers themselves had defied death and escaped the ghetto by hiding amid a wagonload of corpses being hauled out for burial. The pressure on my aunt, an active witness, to stay mum was particularly intense whenever the Gestapo officer my mother identified only as Captain Violin dropped by so he might bow his beloved Mozart to my mother's piano accompaniment while the Schefflers listened from the secret room in the pantry my uncle had built for them. Incidentally, the couple survived the war and eventually made their way to Palestine while my aunt's studied silence later served her well in her work as a research librarian at Johns Hopkins.

There are many shimmering examples of defiance all around us today. The resistance is active everywhere. Profiles in courage abound. The defiant come from every profession, every field, faith and party: from humanities scholars like Kimberle Crenshaw of the African American Studies Forum, to the so-called Godfather of AI Geoffrey Hinton, to myriad journalists such as Kara Swisher and Carol Leonnig and David Remnick and the good folks at NPR, to performers like Jimmy Kimmel and Stephen Colbert, politicians like Mark Kelly and our own Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey, and even Republican operatives like Rick Wilson. Not to mention just about every writer I know.

I will single out the great Gazan poet Mosab Abu Toha, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for his New Yorker columns after launching his English-language career writing for Arrowsmith, who is currently sheltering at Syracuse University. Mosab, who has lost over 30 members of his family to the ongoing genocide, came to prominence when, as a 20-year-old student in Gaza, in an extraordinary act of hope and defiance, he founded its first and only English-language library, every book in it a promise of the possibility for connection and change. That library is now ashes.

The very birth of this country was an act of defiance (albeit imperfect and exclusive) against the forces that oppress and the systems that attempt to entrap the human spirit and the human body. Let's not settle for being inspired, but rather let us be galvanized by the examples of those who fought for human liberty, from Frederick Douglas to Martin Luther King and Ruby Bridges, Margaret Fuller and Lydia Maria Child to Margaret Atwood, from Nanyehi and Tecumseh to Wilma Mankiller and Joy Harjo. Let us aim to have our own names join this honor-roll of the hopeful and the defiant.

"There never was a war that was not inward," wrote the poet Marianne Moore. What we need today is to defy our own inclination to tribalism and to regroup once more around the fundamental principles of a broadly defined humanism, to be reminded that, as William Blake wrote, "everything that lives is holy."

I'll close with a couple of fresh definitions for some old words, as proposed by the German philosopher and founder of Dada, Hugo Ball. First, Ball asks, What is culture? His definition is memorable: “Interceding for the poorest and most humble among the people as if from them the noblest beings and the rich plenitude of heaven are to be born.” He then defines intellect not as a three-digit number. Instead, he observes that intellect is “conscience applied to culture.” Conscience applied to culture. Money and a cultivated intelligence only become meaningful when used as tools for encouraging the growth of juster societies, societies well within our reach so long as we continue defying all that insults our sense of the possible and of our own infinite potential.

Askold Melnyczuk has published five books of fiction. His first novel, What Is Told, was the first commercially published novel in English to bring to light the Ukrainian refugee experience and was named a New York Times Notable. He guest edited a special issue of Irish Pages on The War in Europe available here. His first collection of poetry, The Venus of Odesa, was published with MadHat Press in the spring of 2025. A selection of essays and reviews, With Madonna in Kyiv: Why Literature Still Matters (More than Ever) and Other Selected Non-Fiction, will be out from the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute in 2026.