Seasons in the Vanishing World: Court Observing in the ICE Age

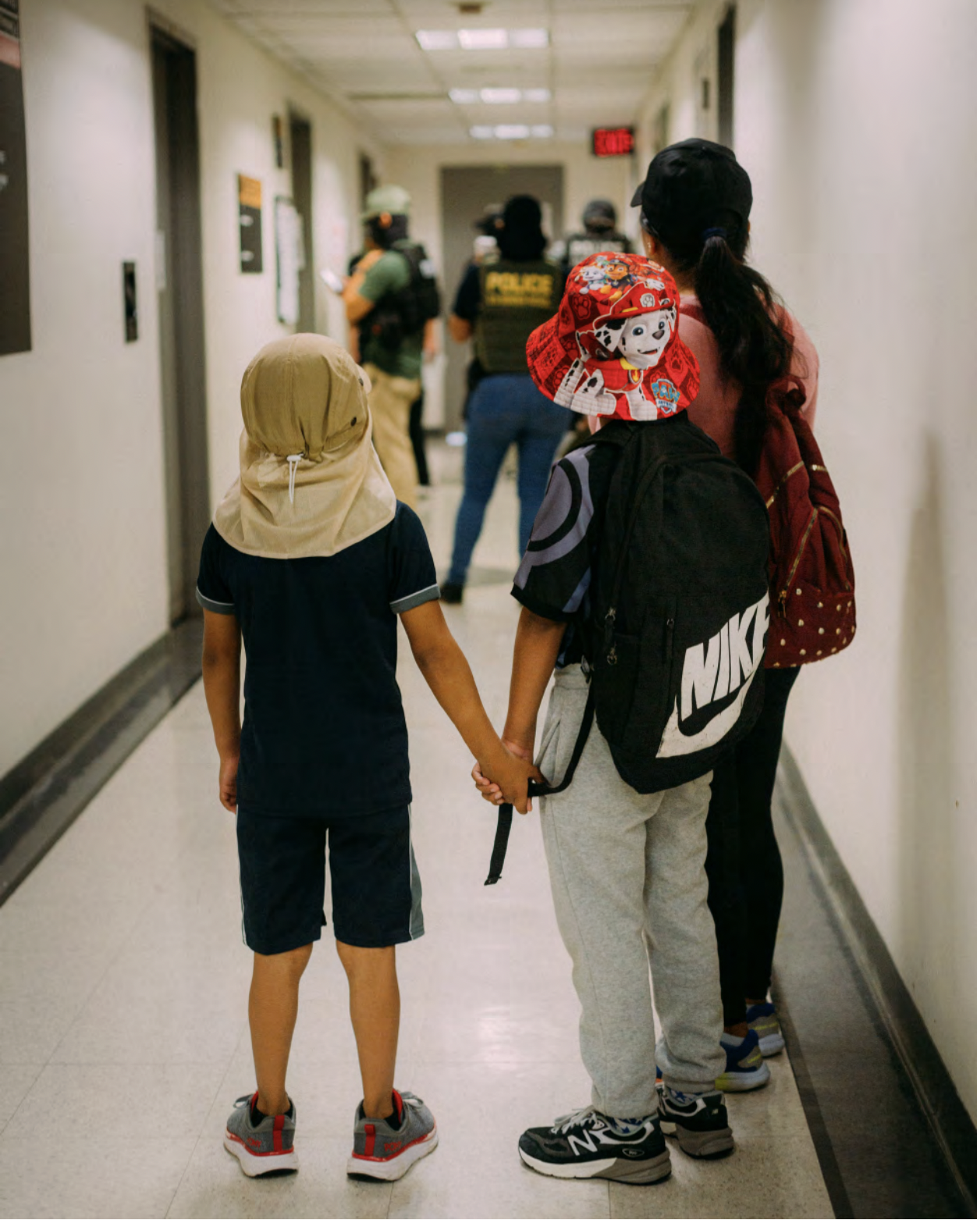

A family of immigrants arrives for their appointment at immigration court, pausing in the hallway when they encounter a group of ICE agents. ICE has been waiting outside of courtrooms to detain immigrants after judges finish hearings. Photo taken at the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building (26 Federal Plaza) in downtown Manhattan, on July 16, 2025.

Photo by Daniel Terna

The armed thugs first came in the spring. The weather was unusually cool and rainy, dogwood blossoms appearing late and withering fast, then the magnolias. The irises had no time for us at all, as if to signal that the world isn’t what it used to be. Beyond flora, too much of the world did persist. Civil war continued in Sudan; Israel’s atrocities in Gaza turned both more brazen and wider spread, with Israeli forces bombing Yemen, killing civilians, raiding Greta Thunberg’s Gaza-bound Freedom Flotilla in international waters, while continuing to target and kill journalists.

My dreams began to involve masked, armed men out hunting, as by then we had seen in videos of Immigration and Customs Enforcement arrests in Los Angeles. In one dream, a masked man knocks on my front door to accuse me of harboring an “immigrant.” In another, SUVs pull up in the intersection by my house and the agents who spill out, carrying semiautomatic weapons, ignore my attempt to scare them off with the low-pressure flow from an old garden hose. They go looking for the unwanted and the superfluous.

Dreaming is no relief, that is. In the 1930s in Germany, privacy was only permitted in sleep, one Nazi official said. Even that wasn’t true, Charlotte Beradt’s The Third Reich of Dreams revealed, a 1968 account of her countrymen’s and -women’s dreams, recently reissued. To colonize the psyche is the nature of evil. The horror is a poison gas; it seeps everywhere.

—

Around the time the rains stopped, the men with sidearms and handcuffs, wearing masks and baseball caps pulled low and dressed in tactical vests that read “ICE” or “Federal Police” or “ERO” (the last, an Orwellian gem, stands for Expedited Removals Office), turned the public areas of the immigration court buildings in Manhattan into an Occupied Zone. The heat outdoors was suddenly furnace-like, relief hard to come by. In my garden, tomato vines wilted. The fireflies disappeared. Leaves in city parks shriveled and fell, not waiting for autumn. A beloved friend passed away. In Gaza, children died not only in bombings and shootings but of starvation. You could be forgiven for feeling that the world had begun to expire.

When the ICE agents tackled a man inside the immigration courtroom, a man who was seeking asylum and was following all the required procedures, when they then hustled him away into the purgatory of the their detention system and then to disappearance, and when they bound and disappeared so many others in the same venue—then, I could hear my ancestors’ shades go restive. My mother’s father’s brother, the Romanian immigrant who wrote the French textbook used in New York City high schools, where he taught. My grandfather’s sister, who adopted a child whose mother, a cousin, had been taken by the SS and sent to the gas. My grandmother’s mother, who made her way from Turkey through most of Greece and then to New York by steamship with six children in tow. Migrants, then neighbors, who lived long lives in their new homelands.

The people who are kidnapped by ICE in my own city are my neighbors. They, like my deceased forebears, are trying to have a life in their new homeland. But they are removed. Disappeared. They had fled their homes and endured an arduous and perhaps dangerous voyage, then applied for asylum in the US and, because asylum seekers must appear before an immigration judge, showed up in the buildings housing immigration courts. What remains a possible path to asylum (one that hasn’t vanished completely) is now so often a gateway to oblivion.

The abductions are not always as brutal as with the man who was tackled, but they are always heartless. Some are wrested from the loving hands of their children, spouses, or other relatives. Others go alone, stoically or wailing, stunned by the instantaneous segue from official legal proceeding to unbridled violence, or awed by the accuracy of their own baleful foreknowledge.

The observer becomes complicit. It is unavoidable, and yet shameful. The observer is complicit because even to speak out against, let alone physically impede, the abductions could prompt the ICE criminals to be yet harsher with the abducted (on a few occasions when many citizen observers were on hand and attempted to form a kind of flying wedge to move the at-risk asylum seeker along the corridor to the exit, ICE agents have simply pushed the observers away and forcibly grabbed their target). In fact, every effort to interfere, even to comment, exacerbates the abducted person’s plight. I do not complain here that the situation leaves me feeling helpless. Of course I’m helpless (the ICE people outnumber observers, and they’re armed). What I assert is shame that I am, every observer is, made part of the crime. This is another way that evil works. Hannah Arendt said it almost three-quarters of a century ago: “The alternative is no longer between good and evil, but between murder and murder.”

Amid the dissonance of shame and helplessness, I started hearing things. Distant voices sounded in my head. A voice came at night from a long-ago colleague, an Argentine woman whose boyfriend had been disappeared by the Junta there in the ‘seventies. “They took me away.” Another voice comes, a new friend, who had said, “the Gestapo took my grandfather.”

Since the Regime took power in January, 200,000 have been removed. The ancestors get no rest.

—

For the Regime and its minions, the world is inherently riven by some recondite force. They feel themselves directed, therefore, to discriminate: on one side are the worthy, on the other, the valueless. This one is safe for now; that one will be disappeared. Arendt wrote that we must share this world, together. She didn’t feel a need to state what happens when we do not share. I will say it: the consequence isn’t merely that we are no longer together; it is that we no longer have a world. And that is the Regime’s goal. Disappear neighbors. Disappear the world.

Our world is vanishing. I mean not the natural world, though it, too, is disappearing. I mean the human one. The moral universe, to take a term from the abolitionist Theodore Parker, via King. Call it what you will. It’s the universe formed by human connection, affection-care-allegiance-compassion, the web from which responsibility emerges. From which morality emerges.

To lose the sense that we share a world is to lose this world. Yet another face of evil is the one that obliterates the sharing sense. The Regime and its minions refuse to believe that the mysterious human capacity to do unimaginable and wondrous things is the source of our goodness. They insist that time runs straight, denying that humans harbor myriad unclassifiable properties that resist the back-and-forth linearity, past-present-future, of ordinary time. The Regime and its supporters reject the possibility of renewal.

Particularity is the tactic by which this Regime practices its evil. As the summer wore on, torrid, nearly rainless, particularity made appearances ever more dreadfully. The numbers of Palestinian children who had died the previous day from malnutrition became a news item—this particular number was perhaps imagined to be graspable, imaginable (although who can imagine a child starving to death, except perhaps the child’s parents and siblings?), and stood in where the overall number of deaths and maimings wrought by Israel’s genocide machine was, apparently, beyond newsworthiness. Prices went up in American supermarkets. ICE detention camps filled up with our neighbors, the number of incarcerated reaching 60,000. Distinctions were made between official ICE detention facilities and ICE processing centers, in both of which abducted people were being held, reportedly in inhumane conditions: little food, no windows, no communication with the outside, few toilets. In the former, officials might be able to visit under federal law, while the latter were off limits to everyone. Abductions by ICE focused especially on Americans who had come from Mexico, Ecuador, Central America, and Colombia. The particularity of birth thus becomes a marker of class in the most mortal way. As with the “torturable class” in Graham Greene’s Havana, one must be either of the nondeportable class or be disappeared.

The mechanics of the evil in the immigration courts are reported, but rarely their weight. Only the most insightful and nuanced of journalistic writing brings that forward (here I must laud Gwynne Hogan of The City; there are a few others, but none so persistent or so consistently humane). Lots of sentimental photographs and prose appear in legacy media publications showing my neighbors as victims; the ICE agents as highly competent, if deplorable, government agents; and observers as well-meaning bystanders. Almost none of these center the neighbors and give them full and meaningful lives; they convey only that the Regime sees some of them as superfluous.

These effusions of evil might well be happening nearby, if you live in a large city. Go and look. Even before witnessing ICE abduct any member of the deportable classes, an observer will sense being in a zone of exception. This is the purpose of the architectonics of the buildings that house immigration courts, I’m sure. Not only the absence of windows, but the glass double doors that separate one nowhere space from the next nowhere space; the broad corridors with a barrier of retractable-belt stanchions blocking access; the narrow passageways leading off the main hallways to no obvious destination; the fixed seating in the waiting areas, bus-terminal-like; the glaring lights and sometimes over-cold air conditioning; the disconnections of the waiting areas from the courtrooms which they are ostensibly for; the locked bathrooms with signs instructing the would-be user to go to a different floor; the walls adorned only by admonitory signs (“asylum fraud is a crime,” “no eating or drinking,” “no photography”); the doors bearings signs reading “No Admittance.” It is a scene from Piranesi’s Imaginary Prisons come to full, twenty-first century articulation.

In person and close by, the brutality by the ICE agents has a heft, a kind of indwelling weight. This is what the media can’t convey. How can the ICE people do this in good conscience?, you wonder. Grab, bind, wrest away from family members, tackle, yank, cuff? Conscience has nothing to do with it, though. In two ways.

First, the building is designed to render the moral compass superfluous. You neither see nor hear the outside world (Manhattan, for all its glass, steel, and concrete, has plenty of parks and plazas with trees; in summer, leaf smells and birdsong waft on the breeze; year round, scents of salt spray and cries of seagulls remind you that no part of the island is far from the sea). Inside the building the city is extinguished. With mortal danger and eerie silences, rules governing the use of every square inch of the space, the personal lifeworld shrinks to the body’s own functions. Even we who are not ourselves in jeopardy, and surely all those who are, are reduced to breath, locomotion, the occasional need to pee. Agamben might call this bare life, Homo sacer. But the concept misses an essential and heartrending ambiguity: the person reduced to Homo sacer always cohabits restlessly with the one who remains Homo sapiens. That is what makes the distillation of the human being into little more than bodily functions so distressing. So exceptional.

Watching the abductions in the building, an observer learns the second key to the consciencelessness. The abductors, the men (and a few women) with faces covered by neck gaiters pulled up almost to eye level, wearing tactical vests and sidearms, josh with one another to kill time, but stare belittlingly at the people who come for asylum hearings and volunteer observers. Try to feel sympathy of some kind. Try to conjure a backstory that would make sense of their cosplay: recent heartbreak, abusive childhood, pregnant wife and heavy debts to pay off, something like that. But then they pin back the arms of a young man whom they intend to disappear, or they berate observers for watching, or push us bodily out of the way. Or call a clergyman “scum,” as they do. Threaten to arrest witnesses. Or actually arrest witnesses, as they’ve done a few times to citizen observers. Humane attempts at compassion fly away. They know what they are doing.

This, I’m sure, is why they cover their mouths. The masked mouth denies narrative. “I see what is before me,” it signals, “but it won’t be spoken of.” We do this when we witness a vehicle on fire on the highway, with passengers in it. Or when we see a just-opened mass grave. We cover our mouths. There is no plausible story here.

In the court building the denial of plausible narrative is a refusal to acknowledge human striving. The ICE criminals’ masks signal that this horror is not to be processed as a human story. It must not be believed.

—

September. Schools have reopened, darkness falls earlier, rain has returned, the subways are once again crowded. Inside the immigration-court buildings, the abductions occur less often than they had two months ago. Perhaps this is a result of a Federal judge’s temporary restraining order (later upgraded to a preliminary injunction) limiting the number of abducted asylum seekers that ICE may hold in their “processing facility” in the building, and requiring ICE to afford those prisoners access to legal services. But that would suggest that the regime abides by judicial decisions, so it’s probably not the main reason.

More likely the reason is unknowable, or senseless. Predictability and plausibility are components of justice. Therefore they are eschewed.

Although abductions are fewer, more ICE agents populate the squads in the buildings. The three squad leaders are the same ones I’ve seen all summer. There’s the over-muscled one; the tiny but preternaturally venom-tongued young woman; and the middle-aged man with a chip on his shoulder, who roughed up and arrested a (petite) court observer in late August; grabbed hard and pushed, but did not arrest, an attorney this month; and this week tackled and threw to the floor a woman whose husband he had just abducted. Many of the foot-soldier agents seem to be new to the job, though, new even to New York. These newbies are keystone cops, clumsy and unsure of what to do. There doesn’t seem to be much for them to do, in fact. They stand around, staring at their phones, until one of the squad leaders tells them to grab one of my neighbors away from his mother or his wife and walk him down the corridor, to oblivion.

The immigration-court buildings remain zones of exception. The rules are made up on the spot, serve only momentarily, and are only valid in an unspecified area. That is, the rules aren’t rules at all, yet they’re binding. When the court observer was arrested in August, for instance, she was walking, with a journalist, in a public corridor. The chip-on-his-shoulder ICE officer accused the two of them of “fucking following” him. The journalist, as she has published, stepped away. Once the observer pointed out, accurately, that she was not following the man, he said he would “fucking beat the crap out of” her, arrested her, wrestled her into a freight elevator, beat her, and took her to detention. Other observers have been banished from the building for standing with a public official (New York City’s Comptroller, Brad Lander, visits the immigration courts as an observer once a week), disobeying an order that had not actually been issued, or taking a photo of an ICE officer abducting an asylum seeker in the public corridor. Elected officials (including Lander) sat inside the building demanding access to the ICE lockup and were rebuffed, then arrested. Clearly, the violation may be perceptual, or nonexistent. For the damned there is decorum; for the regime, only bedlam and intimidation.

As the state of exception in national politics invades dreams, so the state of exception in the immigration-court buildings lingers in one’s own quick. One day I stood in a corridor outside a courtroom, and saw the venom-tongued ICE agent walk up to the courtroom door, tell a priest to step out of the way of a frightened young man and the man’s anguished mother (the priest was trying to comfort them), then walk the young man out, calling to her dimwitted minions to assist. Then I saw her return and do the same to another man, this one without his mother. Each walked down a long corridor to inevitable disappearance. The ICE force melted away. At the courtroom, I waited for the last asylum seeker to see the judge, then I left the building. But the scene wouldn’t leave me, the dismissal of the priest, the dismissal of the mother, the abduction, and the next abduction. I walked a few blocks to join friends nearby. Even though I had seen this evil enacted so many times, it wouldn’t leave me. I was barely able to speak. I was trembling, quivering with rage and shivering with, I think, fear for our world. Nobody is left untouched. No dreams are undisturbed. The state of exception admits no other state.

I had imagined, back during the sauna of July, that September might bring an end to the ICE tactic of immigration-court abductions. Not out of compassion, but because the ICE personnel are so uniformly incurious and cowardly that, I imagined, their attention span would surely be short. Yet, the agents are still taking people, every day.

Around New York, I notice, there are silences. The Mexican and Central American teams no longer come out to play soccer in the city park near me. The lady who has for the past few years sold warm churros outside the subway station near me is gone. The jingle-clink of soda cans and bottles being collected to reap the deposit money is only heard before dawn.

—

Autumn has arrived, and the Jewish New Year. The U Netanah Tokef resonates. “Who by water and who by fire/ who by the sword and who by a wild beast/ ... / who shall be poor and who shall be rich/ who shall be humbled and who shall be exalted.”

I’m not observant. I mean, I don’t do the thrice-daily prayers, keep kosher, wear the kippah (skull cap), observe the sabbath, et cetera. But I am observant in the sense that I observe. I witness. So the U Netanah Tokef prayer, for me, is a notification meant for us witnesses. A message if you will. It says: enter each year with fear and trembling. But with a resolve to make the world new.

I’m thinking at this moment of Arielle Angel’s piece from the summer 2025 issue of Jewish Currents, on rebuilding Jewishness. The essay is really indispensable in its entirety, but here I will take up only the end:

Israel’s genocide is a quicksand; it takes with it not just a failed Jewishness but a failed world order. In some ways, though, the extent of the problem is clarifying. If all is implicated, then we have no choice but to rebuild—Judaism no less than anything else we deem necessary to thrive—so that in time we may find ourselves back on solid ground, in a world made unrecognizable by our efforts.

This, for me, resonates. We are all obligated, Jews and non-Jews—all of us who see a failed world order in the Israeli genocide, the rise of dictatorships, the fury with which the current regime in the US is destroying forms of solidarity, and also the refusal of the powerful to forestall climate change, and more. All of us who see a world-historical moral crisis at hand—we are all obligated. We must build completely new solid foundations on what is now a shifting, treacherous plain of sand. And amid the ruins build the world.

—

It is November now. In immigration court, the crimes continue. Federal attorneys more often seek to have our neighbors sent away to a country that has a so-called Asylum Cooperative Agreement with the US, including Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala, among others, meaning that its leader has cut a deal with our Leader to allow ICE to send asylum seekers there. ICE still takes people away, now sometimes whole families. New camps are being built, the Feds aiming to raise the number in detention to 100,000.

Yet, immigrants remain in our hearts, somehow. More than a million New Yorkers voted for the young immigrant Zohran Mamdani in the mayoral election early this month. A man who has declared himself in favor of all sorts of things that, in any equitable system, would be normal, such as rent control, free bus service and child care, higher taxes on the extremely wealthy, and the arrest of international war criminal Netanyahu should he set foot in the city. Mamdani is (therefore) unremittingly identified by the mainstream media as a socialist and a Muslim. As if those designations were anathema. It is widely understood that the Regime will respond once Mamdani takes office, on January 1st.

How this response will play out is unpredictable. Which must be part of the point: the zone of exception will expand to include the city. And, ultimately, all cities, or at least the neighborhoods that are the Regime’s targets. Thus we, all of us, are put on notice. If we do not stand with our neighbors they will be taken away, removed into the increasing dark. But, if we stand with them too vigorously, we will be said to be fomenting “civil unrest” and the National Guard, the militarized Customs and Border Patrol units, or some other force garbed in federal uniforms and carrying guns will be sent in. The point is the unpredictability of this eventuality, the where and when of it. We must all be stripped of intentionality.

In the end-of-year darkness, it is harder to stand together in any case. Inclement weather, chilly air, the inevitable respiratory illnesses making the rounds, school vacations, holidays—the vulnerabilities of our commonality bring me chills already.

What frightens me most are the blandishments of memory. The winter holidays appeal to memorializing the past: the native people sharing a feast with the new arrivals, Jesus’s birth, the visit of the Wise Men, the miracle of the oil burning for eight days and nights—choose your joy. But memorializing is dangerous. Every concentration camp is a memorial to a new form of an old exploitation, the exploitation of the weak by the strong— beginning with the English camps established for holding Boer and Black South Africans in 1900, through the Nazi camps, to the “refugee” camps for Palestinians after the Nakba, and so on, to America’s immigrant-detention camps today. There is no memory of what we blithely call “history” that is not a memory of destruction. Walter Benjamin puts it this way: “The history that showed things ‘as they really were’ is the strongest narcotic of the century.” And of our century, even more so.

Thus, at the holidays, there will be the customary celebrations of American family life—even though the culture increasingly prizes the obliteration of family togetherness, encouraging more young people to don uniforms and “serve the country” as ICE agents or guards at the camps, which, by design are generally located as inconveniently as possible. And, obviously, by adding to the country’s carceral state (almost two million US citizens are in prisons and jails; hundreds of thousands more work as their jailers) by imprisoning tens of thousands of immigrants to ready them for deportation. Memories of history “as it really was” will bring the soporific unawareness of oppression. Perhaps some crave that.

We must begin not by remembering, then, but by thinking. Thinking of the future we wish. Our job is not to resuscitate a truth about the past which, after all, we can’t share; it is to renew a space that we do share. The future is so often conceived only in terms of time, taking pains to protect our health so as to live longer or wondering how long a career, a home-team winning streak, or our new boiler will last. To be capacious is much harder. To believe that the future will be materially different, that we will therefore be connected on literally different grounds, through a literally different atmosphere, that is a challenge.

To take up the challenge, we will have to think not in terms of the extension of what we (believe) we have, or we had until the bad guys took over. The “postwar order,” “liberal democracy,” “human rights,” or what have you (each of those was honored more in the breach than the observance, in any case). If we are to step up to the current moral crisis, if we are going to continue to talk about arcs of the moral universe, if we are to abolish the efforts to make us all complicit in murder, we must undertake not an act of extension but one of construction. Rebuild. Renew. Build anew.

Philip G. Alcabes is the author of a book on epidemics and culture, Dread: How Fear and Fantasy Have Fueled Epidemics, and essays that have appeared in The American Scholar, The Chronicle Review, LARB, Wrath-Bearing Tree, and other publications. Alcabes lives in the Bronx, New York.