Fanny Quincy Howe: A Tribute

What is a poet but a person

Who lives on the ground

Who laughs and listens

Without pretension of knowing

Anything, driven by the lyric's

Quest for rest that never

(God willing) will be found?

Fanny Howe

From “Far and Away [excerpt]”

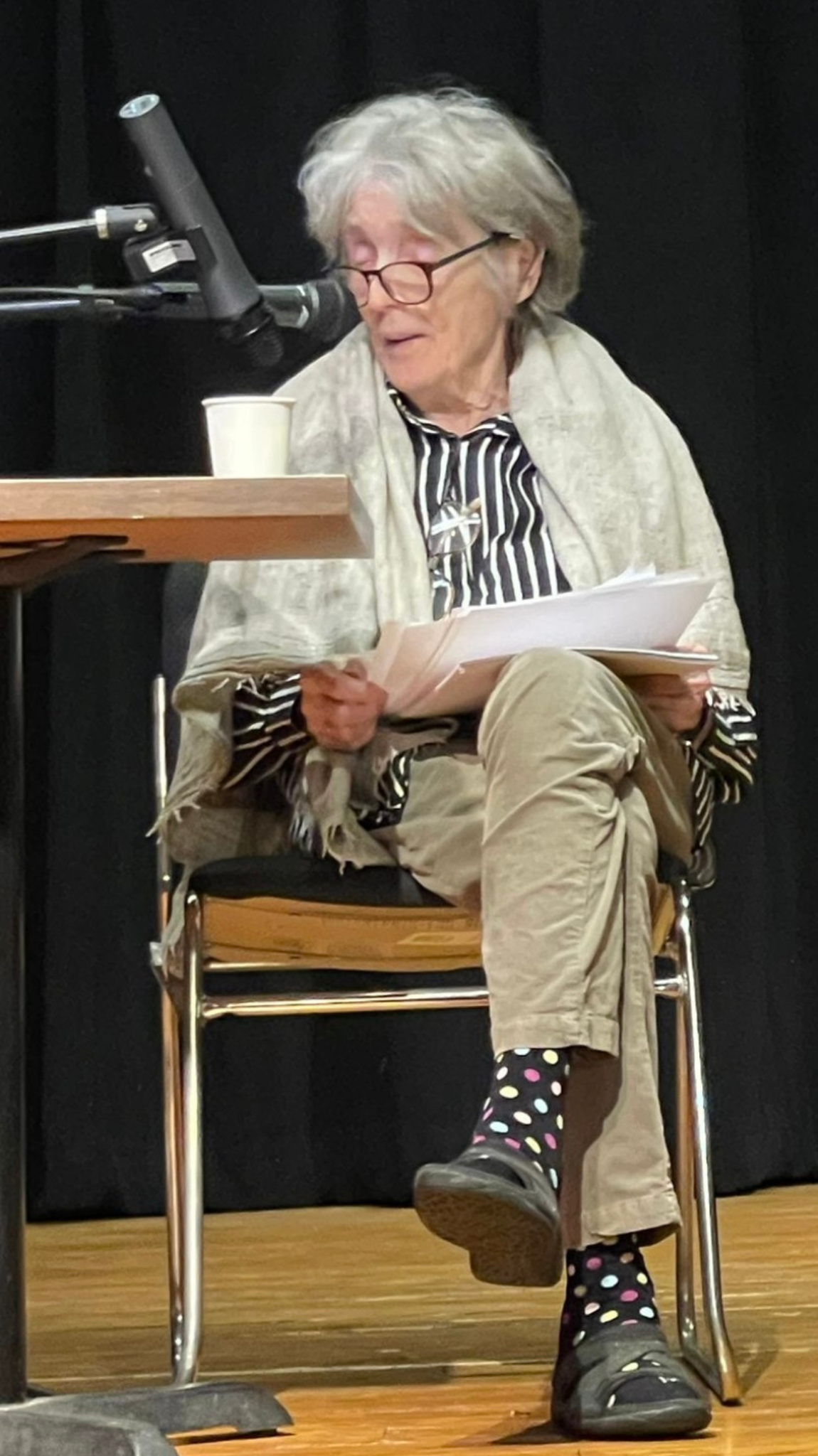

Fanny Howe at Miami Book Fair 2014.

Fanny Howe reading at Blacksmith House Poetry Series on May 5, 2025.

Photo: Marisela Valero.

I met Fanny Howe at the 2014 Miami Book Fair, where she was being honored. She struck me as a fragile soul until I heard her voice, although tremulous, it had great strength. In her poetry reading, she mentioned Ireland several times; her places were full of abbeys, churches, omens. In 2020, when I came to Massachusetts, it was at her home that I was welcomed by the community of poets, artists, and intellectuals of Boston. Her home, I later learned, was everyone's home. She was a home, a sanctuary, a refuge, a den for her friends, where they gathered to talk, to reflect on poetry, art, politics, and everything that these times hold for us. Fanny Quincy Howe, whom Askold Melnyczuk defines as an authentic and original American, was reading her verses two months before she died at the Blacksmith House Poetry Series. It was the last time I saw her, smiling, slow, fragile, with her beautiful gaze of imposing blue skies.

Oh, Fanny, Often it seems that measurements between things are illusory, the Irish bagpipes that were heard at your funeral in Cambridge will remain in the air forever, like a guide, a silence, a prayer, your voice, your verses; the moon get lost in the west dragging her skirt of water.

At Arrowsmith Press, we are pleased to facilitate this gathering of friends and continue to celebrate Fanny Howe. As I received the readings and testimonies about Fanny, some of her verses appeared, or floated in my memory. It occurred to me then to assign a line to each one, or was it Fanny who suggested it to me? Yes, Fanny, always blessing us all with her verses.

Nidia Hernández

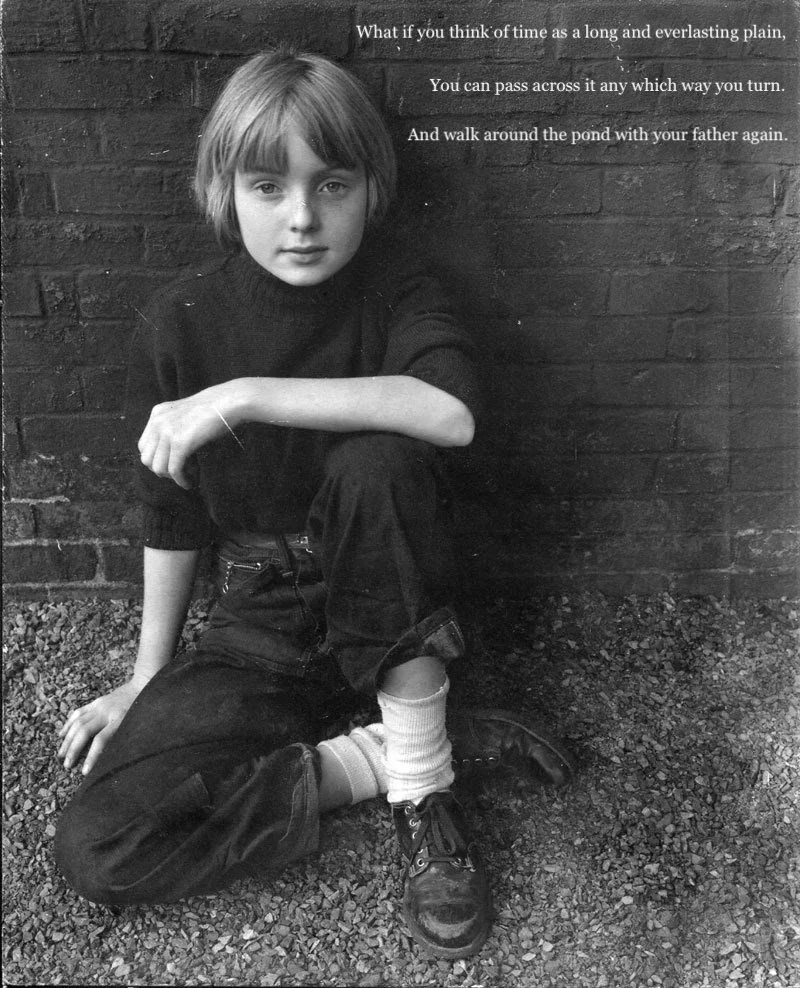

SHEILA GALLAGHER

What if you think of time as a long and everlasting plain,

You can pass across it any which way you tum,

And walk around the pond with your father time and again.

CHRISTINA DAVIS

Sorrow can be a home to stand on so

And see far to: another earth, a place I might know

Christina Davis reads fragments from London-Rose.

Text from London-Rose (designed by Bella Bennett Fraser).

SUE SCHARDT

Often it seems that measurements between things are illusory.

Remembering Fanny Howe

Celebration of Life

Story Chapel, Mount Auburn Cemetery

October 26, 2025

fanny and i drove around together. we called it ramming. i’d pull up to the curb, my car was her chariot. i was her chauffeur. she rode shotgun…except during covid, she’d sit in the back seat, with a kind of sock hanging off the bottom of her face – an assurance, i think, for her daughter danzy who, in those days, didn’t know who i was or why her reckless mother was in my car every time she’d call.

so mostly, she rode shotgun. off we’d go on a ram-around. we’d make up a destination: to find pansies she could put into the little pots on her back deck, or some kind of water i could swim in. i kept a fold-up chair in the trunk so she’d have a place to sit. there was the lollypop cemetery where old shakers are buried. and, of course, the epic whitey bulger /slash/donut ram with three of her six beloved grandchildren crammed into the back seat.

i had the stub of a branch, fat & round, a couple of inches in diameter. i don’t know where it came from. there was a couple of divots cut out of the top, and i wedged it between the dashboard and windshield right in the middle. this stub was our compass.

we’d get onto a long back road with trees of any season passing by on either side. from time to time, we’d be able to see through a break in the trees to a wide field and, with the open sky out there, it was like a deep sigh. we waited for animals to appear. chickens grazing in a field concord (and they were grazing), llamas in carlise, the usual cow or horse. those were good, too.

one night, just before she died, i picked her up – it was late and nearly dark, one of our last rams. we were looking for noodles and a glass of wine. i made a left turn onto a side street off mount auburn when out of the shadows and into the headlights came a fox. i slowed, pulled to the curb. he circled back around and passed just under fanny’s window. i thought in that moment i should roll down the window so she could touch him. then he slipped off and on his way into someone’s front yard bushes.

the air shifted in that moment. i didn’t know what it was. actually, i think i did know. she spoke quietly then, “he’s come up from the cemetery,” and we never spoke about it after that.

air was one of fanny’s elements, as a holding thing, a place of watching, of attunement. we shared the intimacy of air. she writes about the lightness and proportion of it; that the lightness and proportion of air, fanny says, is what some call love.

we came together, fanny and i, at time of fragility – me after a calamity, and she in her final physical decline. i recognize this crossing only in these days since her passing. we were companions.

fanny was as discerning of people as she was of words. why she chose us could seem a mystery. she arranged us into particular circles and vectors. she encouraged us.

i think fanny must have shared this gift of insight with her mother, mary manning. we all now know it was mary who called it early on.

fanny, the tinker. always making a mess, then escaping.

well, she’s made her escape. and we, my friends, are her mess.

she gives us some guidance, words about waiting; the sense there are those we are waiting for. there are those who wait for us.

she prays to the angel of happy meeting.

lead us by the hand toward those we are looking for.

i believe fanny wanted us to help each other. i want us to try. let’s try to help each other.

ANDREA COHEN

Like a sweetheart of the iceberg or wings lost at sea

the wind is what I believe in, the One that moves around each form

Andrea Cohen reads “Margo” by Fanny Howe.

CAROLYN FORCHÉ

When I'm sleeping I don't believe in time as we own it

Carolyn Forché reads “The Angels” by Fanny Howe.

EZRA FOX

If you have to die Puff and visualize

The ozone of heaven

Dear Fanny, don’t worry, I know you’re dead.

You did not want to write your last book, but you needed to. To know that your work was complete and you could do no more. To know that your work is still doing and doing. That writing is a form of suicide, and a form of immortality.

Dear Fanny, you’ll forgive me for stealing your lines, just like you taught me. I’m sorry for the essay I always promised and never finished. I offer you this one instead. You are finally joined with nature and god and the eternal physics of the soul, the wind hasn’t stopped blowing for you, the red and wilding cosmos pulse your song. From where you are (there and here) you have the best vantage from which to read. Reading is best as a necromantic art. I’ve left many of your books unread until now.

Dear Fanny, don’t worry, I won’t embarrass you much longer. You told me not long ago that you didn’t miss writing, that the urge had left you with a soft departure. On the last page of your book you wrote: “In the end I always turn back to the heartbeat of poetry — it’s healthiest when it’s irregular.” I don’t know how to end this letter. We’ve all done our best to say our say. But you always managed to say it best.

BRENDA HILLMAN

The path turned forever

It was that uncertain.

Brenda Hillman reads two poems by Fanny Howe.

ROBERT HASS

I see the moon get lost in the west dragging her skirt of water

Robert Hass reads “The Advance of the Father” by Fanny Howe.

EILEEN MYLES

One perception leads to another.

Eileen Myles reads an untitled poem by Fanny Howe.

RICHARD KEARNEY

Moon ink is too bright to read.

For Fanny (July 14 2025)

You did not leave us when you left this life

but returned again as promised in the living things you loved.

Since the day you died in Boston

You’ve come back to me in Cork.

When the dragonfly –

200 million years old who lives a day –

drew flame

as it crossed my path at Ardra.

When the dolphin jumped over the bow

under the cliff of High Island

where we caught kelp in the motor in June 2010

and had to row hours laughing back to land.

When the curlew circled three times around my head at midnight

on Myross Pier the hour you passed away,

its high cry a parting sigh.

Your yellow bittern. Your first kiss.

When I found the cane you left in the house at Cooscroneen

saying you would return one day to fetch it -

I took it from the rack and walked the field to Brigid's Well,

my hand holding the handle your hand once held

every foot of the way.

JAMES FRASER

Paper or fate?

James Fraser reads “Message” by Fanny Howe.

KYTHE HELLER

I have backed up into my silence as inexhaustible as the sun

Kythe Heller reads “The Monk and Her Seaside Dreams” by Fanny Howe.

JOHN MULROONEY

The moon is moving away

As civilization advances without thought

John Mulrooney reads “Goodbye, Post Office Square” by Fanny Howe.

ASKOLD MELNYCZUK

Sea mist surprises my heavy eyes

I know at last I don't exist

Howe It Is

Fanny Quincy Howe, who died this past July, was the author of, by my count, 19 books of poetry, 19 works of fiction, and 2 memoirs, as well as the director and producer of several short (experimental!) films. More books are promised posthumously. She received an American Book Award in Fiction, as well as the Lenore Marshall and the Ruth Lilly prizes for lifetime achievement in poetry. Over the course of her career, she taught at Yale, Georgetown, Kenyon College, Columbia, MIT, and UMass Boston. Howe’s memoirs and essays stand comfortably alongside Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet as guides to the true meaning of the literary vocation. More about this in a minute.

“Boston writers” notes Shaun O’Connell, who includes both Fanny’s mother and her grandfather in his book on literary Boston as important players on the Boston literary scene across two centuries, “have placed moral mission and spiritual quest at the center of their work.” Certainly this is true of Howe.

I was thinking about it while sitting in Boston’s newest and still evolving neighborhood on the harbor, equidistant between the Institute of Contemporary Art and the late lamented Louis, once Boston’s most exclusive clothing store. The geography seemed an indiscreet acknowledgment of our contemporary world’s proud marriage of art and commerce—it may be the first neighborhood ever to be built on a ground-fill of processed money.

Few writers' reflections about their art have thrilled me more than Howe’s. There is every bit as much poetry in her prose as there is prose in her poetry. Here’s Fanny on the business of novel-writing:

Fiction is concerned with the victims of history, and the writer of fiction shares their plight by wrestling with the torturous clamp of plot. So plot traps the writer with his or her victims, just as history does.

“What does it mean to finish writing a book?”

It means that your plot has defeated you. You have been decimated by its logic, which is finally insufferable. It has worked its spell on you. You have to end the book and get some air.

Listen to how she characterized herself:

….I am at the end of a generation that began with existentialism; that still prefers irritation to irony; and that shares a political position sickened by the fatal incompatibilities between freedom and equality.

(Some of us still use old words like hope, luck, labor, and timing. We are unreconstructed but adaptable.)

There are memorable apercus on Howe’s every page. Writing about Thomas Hardy, she observes: Hardy lived in the years when land was becoming landscape.

So many things about Howe are extraordinary. There is her work, but there is also her biography. Howe’s interest in film making might have something to do with her mother’s directorial achievements but it might equally spring from her father’s early engagement with the art: back in 1928 he went to Hollywood where he worked as an assistant director with actors such as Jimmy Durante and Fred Allen. He then returned to law school, serving later as secretary to Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, whose biographer he became. As a law professor at Harvard, he stood up to Senator Joe McCarthy and spent the summer of 1965 working on civil rights cases in Mississippi. Dig deeper and you’ll find that on her father’s side she descends from the Quincys, who include several mayors of Boston, as well as one president of our poorer cousin across the Charles, and before that, a president of the United States.

You’ll find none of this name dropping in Howe’s memoirs. For this dirt I had to dig.

Her mother founded the Poet’s Theatre in Cambridge, producing plays by gifted undergraduates and young poets such as John Ashbery and Frank O’Hara and W.S. Merwin. Before coming to the United States, Mary Manning had performed at the Abbey Theatre under the direction of W. B. Yeats and is said to have inspired her childhood friend Samuel Beckett, with whom Fanny palled around in Paris, to try his hand at drama.

Out of these strains—her father’s politics, her mother’s aesthetics, and for her own investigations—Fanny forged an art to accommodate her intemperate conscience, reconciling, or maybe heightening, some of the tensions between them with theology. Because there is also Fanny Howe the mystic: Theology is science without instruments. Only words. Therefore words present its greatest dangers.

Elsewhere she writes: I am aware that there is a vision of a just world behind language, sentences, syllables. The evolution of a single word, into syllable, sound, amendment, assertion, tends towards justice. In every sentence you take measure of all the words in relation to each other.

Whether you encounter Howe the poet or the novelist or the memoirist, what’s clear is that you are in the presence of a writer who has found a way of quickening the spirit in an age when others have long abandoned it for lost, smothered by the minutiae of our refined consumerism. Even a brief immersion in Howe restores a reader’s hope in the power of language, of words, to rise to the occasion of our desperate moment. In a siege—and make no mistake about it, the human spirit is under siege, the signs of it too numerous and too obvious to mention—there can be nothing more important.

For several years we were in a reading/discussion group together with several other writers, artists, and philosophers (the other members included Richard Kearney, Mary Anderson, Sheila Gallagher, Alexandra Johnson, Kythe Heller and Sue Schardt). The group met once a month or so at Fanny's modest Cambridge rental. One evening, I don't recall just why, the conversation turned to the idea of zero. I noted that Thomas Merton had written in a letter to the Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz that zero, put in the right place, had power. It turned out Fanny had plenty to say on the subject. Zero, she observed in her essay on Edith Stein, is another name for the omnipresence of God. It is, according to the Zohar, the beginning and the end of all numbers. Any attempt at monetizing it limits its power by fixing a finite measure to something immeasurable. The feeling of powerlessness in the face of a seemingly overwhelming and intrusive surveillance state can be resisted by a recognition of one’s own Omega point — for it is at the level of the interdependent individual that all value is assigned and actualized. All efforts to claim absolute power over another fail because that other will always exist as a continuity from the zero of the start to the zero at the end of time. And the novel knows this.

My last meeting with her took place in mid-June, just a couple of weeks before her death. I'd been asked by a small Cambridge-based literary journal to have a conversation with her about the Gospel according to Mark, Chapter 2. We spent some six months going back and forth on it before sitting down to finalize our response. Two things Fanny said that afternoon keep echoing. Poetry, she said, is "backward thinking." By this she meant that the poet has an intuition, registered first as an inchoate feeling for which the poet then struggles to find a verbal equivalent. Beautiful, I thought, and true.

The other striking thing was her claim that God's aim for us humans amounts to genocide.

I’d like to close with Howe’s summa of what she learned from an early mentor, the inimitable stylist Edward Dahlberg:

What I received from him…was enduring: the sense of the writer’s working life as a vocation. It had requirements. You had to protect yourself from critics, and only read what he would call ‘ethical’ writing. That is, writing that is so conscious of potential falsehoods, contractions, and sloppiness in its grammar, it avoids becoming just one more symptom of the sick State. Dahlberg told me to take a vow of poverty if I was serious about my work. He believed in writing from the heart, not the head, and he insisted on seeing a sensuality in language that was palpable. This was his politics….and to this day I believe he was right. I was one more of his orphans, starved for meaning that he gave me.

Margo

Can she be planted where the corner of the garden’s rocks are down?

I would like bleeding heart or fuchsia to redden the banks

In their brief seasons. Rain, rain, Irish rain.

Diamonds on the stamens when the sun goes blind.

And sweet pea, pale pink, pale blue, perfume.

Please, if you can, make sure there is an ash tree, young and tight and green.

And bring back the smell of turf for the burning. Of her. Of me.

This poem was written for Margo, a very original person who died recently and lived most of her life in Massachusetts. Her most recent collection was published by Pressed Wafer, and she wrote her poems all over letters and papers but managed to remain under-known. This poem was a way of speaking about hers and my strange connection: we both, unknown to each, lived in the same house many years ago on the Irish Sea. We only found out by chance. But this was the fact that bound us, a coincidence really, otherwise called an epiphany. We both loved Ireland, its literature, music, and people, and shared each of them. The poem touches on the pieces of the natural world, its colors, its perfumes, its sounds, and finally its burning when all is said and done. It’s a poem of hope for what is not seen.

Fanny Howe

The Angels

The lassitude of angels

one thing

but how the gold got under

their skin I don't know

I met them

in the Fields of Mourning

where there is

no morning

only the end of night

the dull gold of

transforming suffering:

what is passed on-

as milk is pain-

passed on to those

we love, becoming

nourishment, good luck

for them

Some colors

imply an ease

with indirect experience:

in the Fields of Mourning

the point of each hour

is the dream it inspires

and there

the angels hang out

limp and gold

but suddenly anxious

if told

what trembling joy

their suffering has brought.

Every glance works its way to infinity.

But blue eyes don't make blue sky.

Outside a grey washed world, snow all diffused into steam

and glaucoma. My vagabondage

is unlonelied by poems.

Floral like the slow-motion coming of spring.

And air gets into everything.

Even nothing.

The Advance of the Father

From raindrenched Homeland into a well: the upturned animal

was mine by law and outside the tunnel, him again!

Everywhere I turned the children ran between. “Loose dogs!”

he roared. I remember one sequence: a gulf in his thinking

meant swim as fast as you can. But it was winter and the water

was closed. The mouths of the children were sealed with ice.

After all, we were swimming in emotion, not water.

“Shut up! you Father!” I shouted over my shoulder. Racing,

but not spent, my mind went, “It isn’t good that the human being

is all I have to go by .... It isn’t good that I know who I love

but not who I trust .... It isn’t good that I can run to a priest

but not to a plane .... I lost my way exactly like this.”

Inverted tunnel of the self.

Throat or genital search for the self.

Light that goes on in the self when the eyes are shut.

Uniformity impossible in the psyche’s pre-self

like a day never spent, or how the unseen can make itself felt.

It was as if a boy was calling from the end of a long island.

Docks were vertical and warlike.

I would be on one side of my bed like a mother who can tell

she’s a comfort because she’s called Mother.

Still, we both would be able to see the edge of the problem.

It’s true that the person is also a thing.

When you are running you know the texture. I was clawing

at the palm of one hand and brushing up my blues with the other.

A man who wore his boxers at night remarked that my daughter

was tired. He had nothing to do with anything.

Ahead was the one with magnified eyes and historical data to last.

Know-how and the hysteria to accomplish his whole life.

It was horrible what we would do for peace.

We told him the story of the suffering he made us feel

with the ingratiating stoop of those who came second in the world.

Like a sheep sweating inside

its thick coat, the earth settles

and steams and lives by friction.

Sun ignites the skyline— clean green after rain. Even wood

is sick for the heat inside it to be met

and I associate.

Message

I am afraid

my mind is going

The bloody thieves

are very quick.

You may have noticed I am naked

and sliced by space.

Soon words will be disappeared

and then the Celtic church

and seven friends

I will not name.

One word that contains

so many:

dearth, end, earth, ear, dirt, hen, red, dish, it and

I must examine each part

then cut the ropes without a heart.

Goodbye, Post Office Square

Where wrought iron spears

punctuate the common and rain

turns to snow a minute

I learned six poems

equal the dirt in the road

twenty more make a cobweb

thirty five muddy bodies equal a wall

one and a half jobs don't make a living

great novels are stainglass

their pain is their color

Never welcome on the hill

I looked like a fool with my daily thanks

but the wine was my joke, it was really water

Two stones equal two kisses up there

a leather jacket equals a terrier

In the next world I discovered

a hovel where a naked I writes with a nail

There you're as small as zero, the hole in the wall

the mouse goes in

with a whorl of cheese

for the littlest glass-cutter to eat

To paint one rose equals a life in that place

and on the thorny path outside

one cathedral is equal to the sky

Bigelow Chapel

Mount Auburn Cemetery