David Souter: A Reminiscence

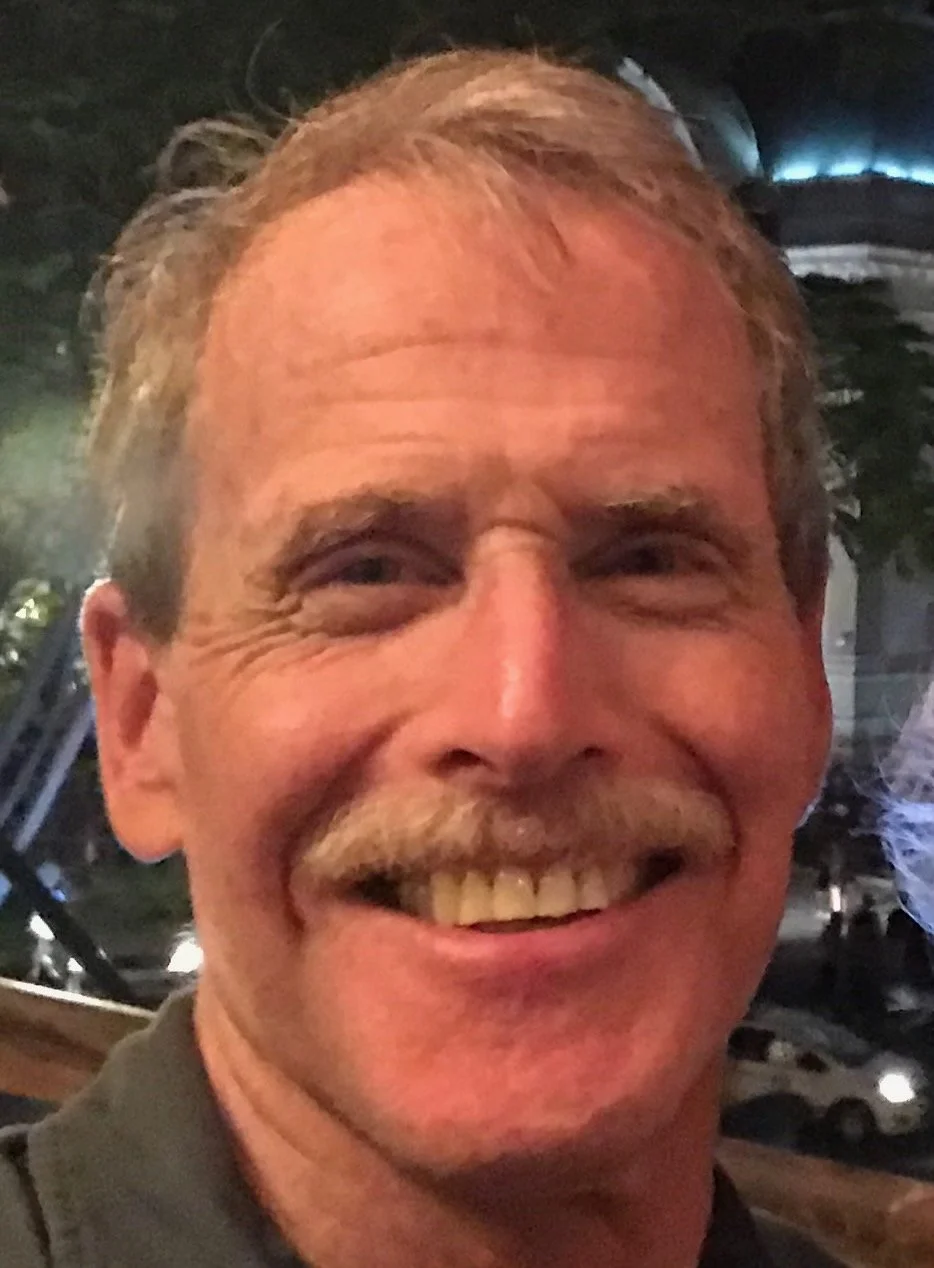

Associate Justice of the New Hampshire Superior Court David Souter in 1983

I met David Souter long before he became a public figure.

It was the fall of 1975, and I was in my last year of law school without a clear idea of what I wanted to do with myself. I spent that Thanksgiving with friends in an old farmhouse outside Concord, New Hampshire; one of them mentioned that the state Attorney General’s office was going through a turnover and hiring recent graduates. Friday of a holiday weekend isn’t exactly the best time to try and schedule a job interview but I called, thinking it was worth a try.

The phone rang for a while. I was about to hang up when a soft voice said, simply, “Hello?” I launched into a prepared explanation: visiting briefly, only just heard about the opportunity, interested in public service. There was a pause, after which Deputy State Attorney General David Souter, alone in the office on a long weekend, said, “Sure, come on in. I guess I’ll talk to you.”

For obvious reasons, I’ve remained grateful ever since for whatever youthful conceit caused me to make that call. The office I joined was regularly in one political crossfire or another generated by New Hampshire’s then Governor Meldrim Thompson. Thompson was a carpetbagger, originally from Georgia and Florida, who had been a member of George Wallace’s American Independent Party. As it turned out, he was a portent of Donald Trump. He thought the Attorney General should be his own lawyer, not the state’s.

By the time I reported for my first day on the job, David Souter had become New Hampshire’s Attorney General. He was only five or six years older than most of us, but an undeniable role model. We were generally just out of school, in our first law jobs. We’d been trained to analyze text, argue by analogy, and split hairs within an inch of our lives. But watching David Souter we saw what it meant to withstand pressure—how to maintain integrity while serving a political client.

All kinds of misconceptions attached to the man once he became the focus of national attention: he was a weird and reclusive New England bachelor according to congressional Democrats who opposed his nomination (and who soon came to thank their lucky stars that they had failed). Reporters sought to confirm their carelessly formed caricature of a remote intellectual, disconnected from ordinary Americans.

I had learned this was nonsense even before I started work. What followed my impulsive phone call was anything but a conventional law job interview. As the late November afternoon darkened outside the windows, we sat surrounded by metal filing cabinets in the deserted offices of New Hampshire’s State House Annex. Except for those surroundings, it was like finding oneself seated at dinner next to a companion who can engage on most any subject and is genuinely interested in what you have to say. We didn’t spend much time on the usual law and career topics, abandoning them for other areas of mutual interest. The future Justice Souter didn’t want to know what I thought so much as how I thought. He applied a sort of relentless courtesy to see if I could defend a position on whatever issue surfaced in our conversation. He wanted to figure me out as a person. I emerged almost two hours later, scratching my head, exhausted, strangely energized.

My experience was not unique. In an interview with C-Span at the time of the Supreme Court nomination, my former colleague Bill Glahn, who had left a law practice in downtown Boston to join the office, remarked “Almost anyone who David interviewed will tell you they came to the office because of him. The things that he found out about you and the things that he got you to talk about were much different from the normal interview.”

The man who was tagged a reclusive loner was nothing of the kind. He pursued human connection and cared about the personal qualities of colleagues with whom he would be spending time and sharing challenges. He made sure we would be a cohesive fit and enjoy each others’ company. Five decades later, when the chance arises, we still do.

The conventional thinking that misjudged the man also misunderstood the judicial nominee. A claim, still parroted today by Republicans, was that David Souter was a “stealth candidate” who betrayed the promise of conservatism. Their disappointment was the fault of White House Chief of Staff John Sununu, who assured anyone within earshot that David Souter’s nomination was a “home run” for Republicans, a phrase understood to mean that he would vote to overrule Roe v Wade. They should have paid less attention to Sununu, and more to the nominee himself.

At the outset of the Senate Judiciary Committee hearings—in response to questioning by then Senator and committee Chair Joseph Biden, the nominee did not mince words: “… the due process clause does recognize and does protect an unenumerated right of privacy.” While he refused to be drawn into a discussion of how privacy might determine his approach to any particular case, his testimony was a clear signal that Roe might be constitutionally sound. For those expecting a “home run,” it was an explicit rejection of the emerging fad of originalism and its reliance on the fact that the word “privacy” does not appear in the Constitution.

In case his reference to due process was too abstract for Senators on the Committee who were given more to making speeches than asking questions or listening to answers, he spelled it out unmistakably in an exchange with Senator Patrick Leahy of Vermont:

“Let’s assume that we found that the establishment clause had a very narrow (originally) intended meaning. Do we ignore…the development of the law for the last 40, or 200 years? The answer is no. We don’t deal with constitutional problems that way.”

So, at risk of losing support from the party that had nominated him, David Souter telegraphed his punch. His respect for precedent, a subject on which he also touched at some length during the hearings, would not bind him to the speculative intent of the founders. Nor would he disregard more than two centuries of jurisprudence, or societal change.

The irony is that David Souter did provide a classic conservative sensibility to the Court. Many Republicans may not have gotten what they wanted—but they certainly got what they should have wanted. A serious attack on Roe came to the Court in 1992 in the case of Planned Parenthood v Casey. David Souter was one of the three authors of the majority opinion. Here, in sixteen words of plain English, is the core principle on which that opinion is based:

“Our obligation is to define the liberty of all, not to mandate our own moral code.”

A more eloquent statement of classical conservatism, not to mention a sounder rebuke to right wing fundamentalism, is hard to find.

Republicans who had relied on Sununu and failed to do their own due diligence during the confirmation process certainly started to pay attention once Justice Souter was on the bench. What followed was an acute case of buyer’s remorse. Failing to recognize that their complaints were in the nature of self-inflicted wounds, as well lacking in substance, conservatives adopted a mantra: “No more Souters.”

That’s a phrase they should seriously rethink—never more than today. His opinions have a quality of understanding and foresight that is sadly lacking in the Court’s present majority. Here is what he wrote about the effect of money in politics in the case of Nixon v. Shrink Missouri Government PAC:

There is little reason to doubt that sometimes large contributions will work actual corruption of our political system, and no reason to question the existence of a corresponding suspicion among voters. [528 US 377, 395]

Those words were written in 2000, the same year he dissented in Bush v Gore. By contrast, in Shrink Missouri Government PAC, Justice Souter was speaking for a six member majority a full decade before Citizens United v Federal Election Commission. The Court, without his voice in 2010, would have done well to remember his all-too accurate prediction when it handed down Citizens United.

The traditional purpose of Supreme Court jurisprudence may generally be defined as the defense of core constitutional values in the midst of high-stakes conflict. Here is what David Souter said in an interview in 2012, four years before the then-unimaginable election of Donald Trump:

What I worry about is that when problems are not addressed, people will not know who is responsible. And when the problems get bad enough, as they might do, for example, with another serious terrorist attack, as they might do with another financial meltdown, some one person will come forward and say, ‘Give me total power and I will solve this problem.’

He continued, “That is the way democracy dies. And if something is not done to improve the level of civic knowledge, that is what you should worry about at night.” Few commentators, if any, can claim to have seen then what is now distressingly obvious.

This brings us to Bush v Gore, the most controversial decision issued during his tenure.

The case reached the Court after various counties in Florida had badly mismanaged vote tabulation and the Florida Supreme Court had ordered a recount to clean up the mess. A five judge majority of the U.S. Supreme Court barred the recount from proceeding, thereby awarding Florida’s electoral votes, and the presidency, to George W. Bush.

The majority decision, issued per curiam (and therefore unsigned), reversed the Florida Supreme Court’s decision requiring a recount, even while effectively conceding that the Florida decision was based on the correct constitutional standard. The Supreme Court majority ruled nevertheless that the Florida decision was defective because it didn’t set forth specific procedures to determine voters’ intent.

The Souter dissent cuts through the pretense. He made the obvious point that Florida’s reliance on a voter’s intent was a sound and proper test for any ballot. He noted that Florida’s standards in determining what should be a “rejected” ballot, i.e., one to be discarded, was “well within the bounds of common sense.” And finally he pointed out that if his colleagues really believed the Florida decision lacked sufficient detail, all they had to do was remand the case with an order to provide specifics.

Bush v Gore probably did more to undermine the credibility of the U.S. Supreme Court in modern times than any decision that preceded it. It is true that a remand in the heat of the moment, with the attendant possibility of a recount favoring Gore, would have been a bitter disappointment to Bush adherents. But both the logic and constitutional correctness of reaffirming Florida’s right to supervise the choosing of its own electors, so long as it did so honestly, would have garnered far greater acceptance in the medium and longer run.

That plain-spoken dissent is one more reason to have regretted his retirement from the Court at the young age of sixty-nine. In truth, the honor of being appointed to our highest court was not enough to overcome David Souter’s distaste for Washington DC, his antipathy to trappings of power, and a strong aversion to what Marcus Aurelius centuries ago labeled “the clacking of tongues.” His disenchantment, which never faded completely after the 2000 election, seems almost quaint today with a Court whose “conservative” majority is marked by arrogant disdain for personal ethics, crass pursuit of the trappings of wealth, and intellectual dishonesty.

In retiring when he did David Souter reminded us that we had better be careful how we spend our limited time on this earth. In his relationships he conveyed the clear message that friends are more important than fame or public acclamation. As a judge he exemplified the principle that legal decisions affecting a single person, or millions of citizens, must be as honest as one can humanly make them.

In his company it was impossible to forget that if you take yourself too seriously you will be lost. Another member of that small public office I joined fifty years ago, and later a Federal District Judge in New Hampshire, Steven McAuliffe, put it this way: “David Souter is a humble and insatiable student of life….He laughs easily, and most easily at himself.”

It’s true. For the foreseeable future, there will be no more Souters.

Andrew Grainger is a retired Associate Justice of the Massachusetts Appeals Court. He has been designated a Fulbright Senior Specialist by the U.S. Department of State. He and his wife, Kathleen Stone, have taught courses and seminars on U.S. law in numerous countries in Europe and the Far East. His writing has appeared in WBUR’s Cognoscenti and the Boston Globe.