Return

For Fanny Howe

I traveled to Kalaupapa, the Hawaiian Settlement for People with Hansen’s Disease (also known as leprosy) as a way to reconcile being cancelled. I wanted to bring myself intentionally and deeply into the experience of exile. Coming to this land was a way to begin healing, and to remake myself, my work, and my sense of place in the world.

This had once been the world’s largest confine for people with the disease. It was established in 1866 on an isolated peninsula along the coast of Molokai, one of the smallest of the Hawaiian Archipelago. It is still an active settlement, with the few remaining patients of those who chose to stay on after restrictions were lifted in 1969. They are quite elderly, and free from the disease that brought them here. They come and go as they like.

A cure for Hansen’s Disease came with the introduction of sulfone drugs, which effectively eradicated the bacterium causing what is now understood to be a chronic infection. By 1946, patients were receiving this restorative treatment and, while disfigurement could not be reversed, the afflicted no longer lived with fear of the disease or the punishments of society: criminalization, banishment, and—in Medieval times—castration or execution.

Before the cure, the diseased were culled from society, exiled to “colonies,” leprosariums, asylums, to isolated mountaintops or remote islands. The people indigenous to the peninsula had been there for nearly 1000 years. They called their home Makanalua.¹ From above, it appears as a wide spear tip piercing the sea. The first settlement for the exiled, Kalawao, was established on the eastern shore. They were eventually moved to the western shore called Kalaupapa. This became the permanent, present-day settlement.

Though never widespread on the mainland United States, Hansen's Disease proliferated in Hawaii beginning in the mid-19th century. It was just one of the devastating viruses and infections brought to the islands by merchant sailors, beginning with the crew of Captain James Cook in 1778. “The Act to Prevent the Spread of Leprosy,” adopted in 1865, a year before the colony at Kalawao was created, called for the arrest and confinement of any Hawaiian suspected of having the disease. Some turned themselves over voluntarily, others were pursued by sheriffs and constables across the islands. They were assembled, their names neatly recorded in a book of the banished, and then loaded onto ships that carried them across miles of open water to their final destination. The men had been given a blanket and a shovel, women just a blanket. In a petition by a group of Native Hawaiians opposing the State Legislature’s action, the consensus was that their kin were taken away “not for any good, but…thrown away like pigs in consequence of (the) evil law…”.

The first dozen exiles² to arrive began a lineage of what would eventually number 8000 people spanning more than a century. They made their landing on a rocky beach and climbed a steep incline to where the land flattened out into a forest. Their arrival was unexpected, and details of how the native Hawaiians received these newcomers is lost in time. Government-appointed overseers came and went, and there were others whose vocation was to care for “the lepers.” Father Damien, a carpenter priest and the first full time clergy in the settlement, began his 16-year term by building coffins for the dead. He eventually succumbed to the disease. Seven Sisters of Saint Francis, under the direction of Sister (Mother) Marianne Cope, arrived from Syracuse, NY in 1883 to create the Bishop Home for Unprotected Leper Girls and Women, a sanctuary for the community’s most vulnerable, who were under constant threat of abuse. Both Father Damien and Mother Marianne were beatified by the Catholic Church for their work here. Over decades, churches were erected, as well as schools, a hospital, sports fields and Paschoal Hall where entertainers—Bing Crosby, Paul Robeson, Shirley Temple—would occasionally perform.

Over more than a century, and in spite of the progression of their physical decay, a thriving community took shape. The patients, as they came to be called, lived in the paradoxical state of exile, carrying the pain of separation and, at the same time, living freely on land and abundant with fruit, sweet potato, taro, and wild boar. The bounty of the sea was always a short walk away. Kalaupapa was both a prison and a sanctuary. Out of abject suffering, the patients settled into the pace of give and take relations. Some of them married, and the children born were taken and returned, orphaned and tainted, to the society that had banished them.

The evolution of social separation was of central concern to French philosopher Michel Foucault, who examined societal response to “disease(s) of the social body.” In a lecture at the Collège De France in 1974, Foucault explores the interrelations of structures devised for the purpose of confinement: e.g. colonies for lepers, prisons for the criminals, asylums for the insane, surveillance of deviants. His complex and thorough reasoning always points back to inherent dichotomies: “a kind of symmetry” between the one side inflicting punishment and the other, the condemned. “Both disturb public order,” he asserts.

Simone Weill’s work three decades earlier brought sharp attention to the subjective separation of people in a society. “(It is) impossible to feel equal respect for things that are in fact unequal,” she wrote in 1943, “unless the respect is given to something that is identical in all of them.” Weill believed there was “something sacred in every human.” She described this as “a center in the human heart longing for an absolute good.”³

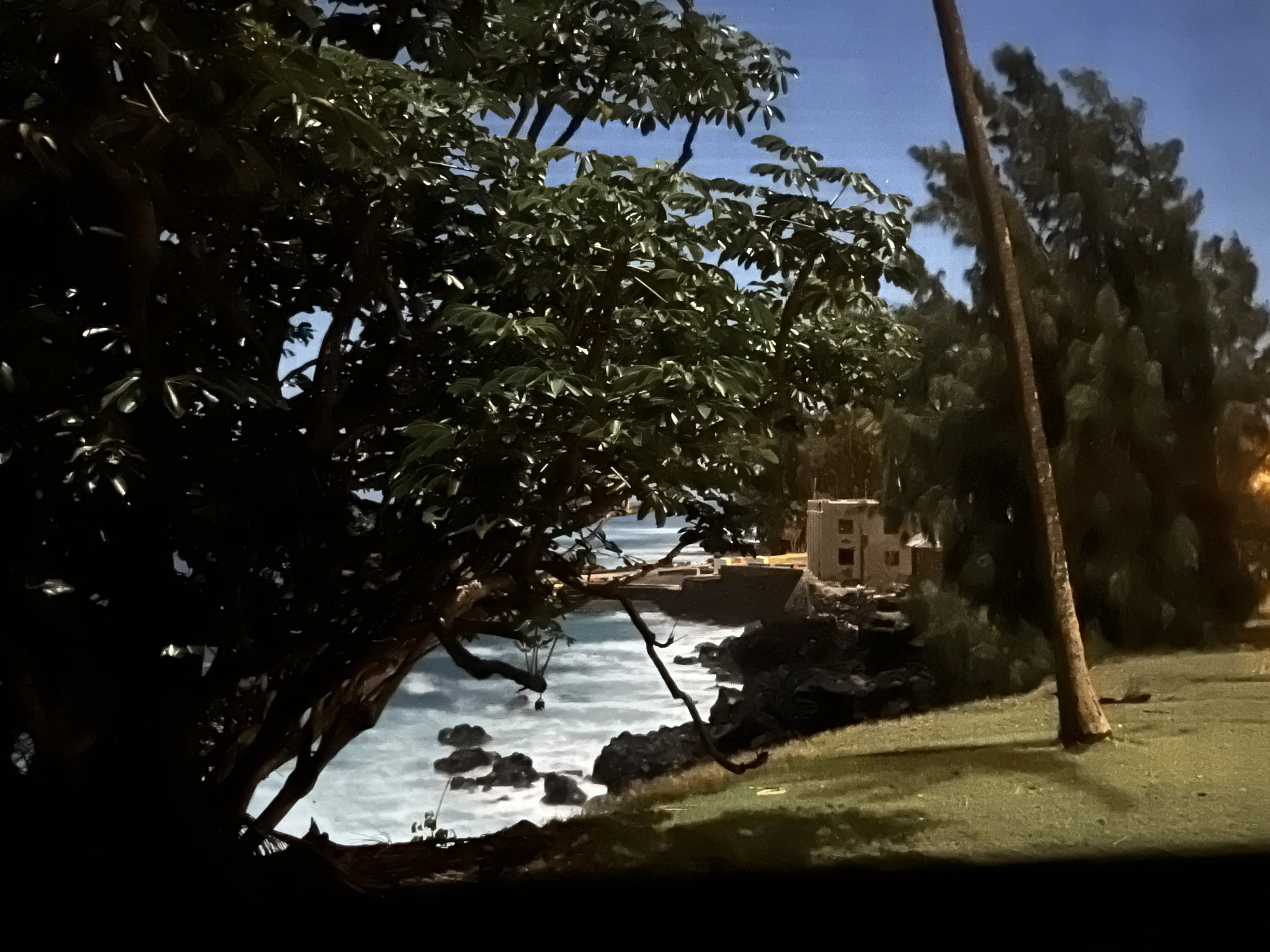

I was not the first to visit this place, not the first to try to describe it. From Honolulu, it takes just under an hour by small engine plane to touch down on Kalaupapa’s single runway. As we approach, I watch out the window with my binoculars, twisting distant shapes into focus. Black rocks scatter along the edges of the peninsula, and a dense overstory covers the middle. A shape that rises above the treeline is what remains of the volcano that long ago spat out what became this land. Kalaupapa is hinged to the island of Molokai by the highest sea cliffs in the world. These pali, as they’re known to inhabitants, reach nearly 4,000 feet, towering like sentinels keeping watch over the land and everything living beneath them. A narrow switchback trail slaloms up from the beach, two hours walking bottom to top. In earlier days, those attempting the trek would find a locked gate. These cliffs, together with the vast surrounding sea, are the reason it was chosen. It was inescapable.

Kumu Keala, a keeper of knowledge from the Big Island of Hawaii, explained to me once that every aspect of the physical landscape is considered an ancestor, and is therefore named: the mountain, its ridge, the clouds. In this particular outcropping on Molokai, he told me, “The exiles were brought into “the” (kau) “leaf” (lau) of “the mother that is the land” (papa).” In the earliest times, the name of Molokai itself was Pule O’o, a reference to the “powerful prayer” that, in traditional lore, once repelled enemy invaders from its shores. The wisdom of interconnection between all things is carried in the language, Kumu told me, and in this way, the land is where “the healing sense begins.”

I stand on the grassy field of Kalawao looking out at hummocks that rise, camelback, from the cove below where the transport boats of the early exiles anchored. Beneath my feet are the remains of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of the first sent here to die. I imagine them piled together into this single grave, the dirt absorbing their blood and bones, the land and the people made one and, together, made holy. This is the starting place.

There is a road leading deeper into the forest. It is rough and rutted. Walking may be the best way to travel the two and a half miles west to Kalaupapa. Through the trees, I begin to make out artifacts of the natives who’d greeted the first exiles. Their stone walls stand in neat symmetries, a large rock curving into a gentle recline where laboring women lay in childbirth, and there’s a water catchment system just off the road, built in Father Damien’s time. Covered in vegetation, it rises out of the shadows as a strange, animal-like presence. Far and near, birds call back and forth with unfamiliar songs, or alone with intervals that wait for a response. Nutmeg Mannikin, Myna, Shama…I try to whistle a match, but their tonal ranges surpass even the span of Beethoven’s keyboard, and seem to my unaccustomed ear to be more complex than the robins, jays and warblers back home. On this slow crossing of the land, marking my steps to breath, these songs are all I hear.

A feral pig (pua’a), sturdy in its prime, crosses at a distance in front of me. Three piglets scurry along behind, determined to keep up. I come to a sign on the right with an arrow pointing northward towards a narrow path into the brush: “Given Grave” is written in neat print. I walk a gentle slope to the top of the old volcano I’d seen from the sky, considered by the living and those long dead to be a sacred burial place. Peering down into it, I see a small lake far below, feel a longing to swim in it, and I wonder if I might find a path to go down. There are headstones on the edge of the crater, and a belief that the ancient ones brought the bones of the dead here—perhaps to drop into the water below, or put to rest in small caves that pock its descending and forested sides.

I turn to head back down the path, and come upon a battle underway. A bee, snared in an enormous web, is in a live or die struggle with an equally enormous spider. I vacillate—should I let nature take its course? I don’t, and pull a sturdy stick off a bush. I scrape the bee away from its fate and lay it on a tree leaf, spitting on it a few times to help it rinse off the sticky spider glue, then continue on down to the Kalaupapa road. I didn’t know then that the bee and I would meet again.

Stray cats come out from their hiding places to sit atop a stone wall and watch as I enter the settlement. I pass by well built, plantation style wooden houses, home to those who remain here. They intermingle with many more long-abandoned structures that are slowly collapsing in disrepair. There is a two room post office, four churches—Catholic, two Protestant, and Mormon. A single resident priest presides over 6am daily mass at Saint Francis where, it’s said, Father Damien himself climbed up onto the altar to set a statue of the saint just below the crucified Jesus. The other churches are not active, but destinations for pilgrims coming from around the world. The single story health center sits alongside the water’s edge and serves patients in need of closer attention. This present-day settlement was established in 1888, and it continues to be home for the few remaining patients, their caretakers, and National Park Service workers who are now the stewards of this land.

Once a year, everyone crowds onto a wide concrete pier on “Barge Day” to welcome the vessel and crew bringing large appliances, vehicles, gasoline, and bulk supplies. The rest of the year, this spot serves as an unrivaled swimming hole, except on winter days when storm surges turn the normally serene water into a washing machine. Food is flown in once a week or so, and only full-time workers and patients are allowed into the small grocery store with its wide wooden porch. Next door is the gas pump, where those with cars are allowed four gallons. Driving at seven miles an hour, it takes about twelve minutes to make the full circuit of the settlement, with its boundaries demarcated by cattle guards that unaccompanied visitors are not allowed to cross.

Visitors are restricted in other ways, allowed in only under “sponsorship” of a full time resident or worker. Children under the age of 16 are not permitted to enter at all. I’m told this is out of respect for the patients and their children taken away at birth, yet another of the cruel measures meant to try to contain the disease. There are day pilgrims, and researchers who study sea life, plants, insects, or the rare offshore coral colonies. With the one full time priest, there are two nuns, Sisters of Saint Francis, who represent Mother Marianne’s uninterrupted, five generation legacy of care for the patients. Weekends are quiet, as many of the workers who manage infrastructure and operations head home. Some walk the nearly five miles up the cliff path, while others catch the prop plane that skips them “topside” in a matter of minutes. Most people who spend any time in Kalaupapa describe it as a paradise—“life-giving,” as one of the Sisters described it to me. The settlement will continue to operate until the last of the patients passes. No one knows for sure what will become of it after that.

Kalaupapa, like Kalawao on the opposite shore, has a burial ground aptly named Papaloa, which translates to mean “long, flat area.” It spreads for a third of a mile along a narrow green running alongside the airport road. Unlike the Kalawao’s mass grave, each of the thousand or more buried here is marked. You begin to spot the headstones on your left after you’ve passed Saint Francis church, just beyond the empty Mormon chapel. There are white obelisks gleaming in mid-day’s sun, lava rock mounds, and simple headstones embedded in the dirt or standing up. Someone has etched into the stones—English, Chinese, Japanese—a name and a date, some with epitaphs or carved images. One marker, its letters worn away, is sunk deep into the body of an ancient plumeria tree that’s grown up around it. They intertwine into a single formation and, in this, there is a message for me: “This land embraced the outcasts; those who are banished are held and healed by this land.”

I spent quite some time wandering amongst these graves, studying the memorials, and conjuring fantasies of the named and unnamed. One day, feeling hot in the afternoon sun, I walked through the cemetery to the shoreline just past the graves to find some relief in the sea. At a distance across the sand, I saw what looked like a large animal lying dead. I pulled out my binoculars, approached slowly for a more careful look, and found it was one of the endangered monk seals that come here to breed. Their Hawaiian name is Īlioholoikauaua or "dog that runs in rough water." They are very big dogs. There are monitors appointed each year to count the new pups and their numbers, posted on a public board, are a source of pride for the community. My heart sank, and I began to assess details of what would be a sad report. I took a few steps closer, holding the animal in the lens of my binocs, and saw the creature lazily open one eye. She groaned, and rolled over. The monk (and I) had another day.

Several years ago, Yo-Yo Ma flew into Kalaupapa on a prop plane bringing his cello. He set up a folding chair in the midst of Papaloa’s graves. But for the dead, his audience was small. They sat expectantly under a pop up tent, protected from the sun. Ma spoke briefly, describing how Pablo Casals chose a self-imposed exile from Spain in protest of Franco’s dictatorship. The separation from his homeland lasted 23 years. To mark his separation and feelings of loss, Casals chose to begin every performance with a traditional Catalan lullaby, “El cant dels Ocells” (Song of the Birds). “Some of the departed are still with us,” said Ma. “This is a way to call them.” He struck with his bow and began to play. A single strain wended into the stirring breeze, moving beyond the tree line to meet the rhythm of the surf pulling back and forth across the craggy shoreline. Ma moved slowly as with the water, rocking his bow across the strings, pulling one phrase and the next into a strain of pure longing, opening way to memory. All that is above and below quivers into one vibration, his music joining with the sounds that have always flowed throughout this sacred place.

Exile, or “cutting away,” has been in practice for tens of thousands of years and takes many forms: punitive, political, medical, ritualistic. The central idea is the same: to remove what is diseased, what threatens the larger body, or inhibits growth. In contemporary society and with the speed of technology, banishment has taken a new, more efficient form in cancel culture, surging from the margins of society with the power and intensity of those who had long been silenced. In 2006, the #metoo movement began to call out serial abusers who had too long used their power to harass and assault others, most often women. Similar grassroots support and public outrage began to spread to other mass actions. While there's no straight line linking these movements, #metoo shares powerful DNA with Black Lives Matter's rise in 2013. There was now social pressure to remove offending individuals from positions of power and speak out against oppressive forces. Over the next ten years, public support for retribution, reparations, and social justice surrounded the Supreme Court's 2015 ruling to strike down all bans on same-sex marriage, and a 2020 decision that extended civil rights protections to transgender people.

There is, of course, no comparing the experience of today’s social exile to the criminalization and rejection of people with Hansen’s Disease. Still, there is a shared intent that the offender be erased, no longer engaged with or endangering the larger whole. Somewhere along the way, with the “good fights” still continuing, #metoo seemed to have been, too often, co-opted and turned into a pervasive, unfiltered weapon against anyone who caused discomfort or offense. The fate of today’s sociotech offender is not determined by consensus or due process as in the days of old, but by social media engagement, often reinforced by sensational, quick reporting. Anger is undeniably intertwined with the impulse to punish or seek retribution. Beneath anger, at a deeper human level and harder to discern, is fear. Further still and at the root, it is grief that provokes fear and anger. Twenty years later, considering what has been gained, some of us are also asking what of our collective humanity has been lost along the way.

To be cut out, suddenly and unexpectedly is to fall into a state of disbelief. It can be impossible to explain or understand what has happened, because you yourself cannot see it clearly. Words will not come, perhaps not for a long time. Removed from your people, you lose your ground and, without language, you are bewildered or “in the wild,” as poet Fanny Howe described it. You’ve entered that existential paradox, dead to the world as you knew it, but still alive.

There are many people in virtually every sector of our working world—academia, the arts, government, public media—impacted by cancel culture. My experience of banishment is not unique. And yet it’s led me into a singular and continuous evolution. Having lost the story of “who I am and what I do,” without title or place, I was freed. Over time, I began to recognize myself as a ghost, moving in the margins, somewhere like Michel de Certeau’s “mystical space,” the path for those who want to get lost, who seek, without knowing to “restore the ineliminable distance…, the movement of love and the movement of loss.”⁴ Neither inside or out, my advantage has become that of an observer. I began to prefer invisibility to all other states.

The loss of bearings also meant a loss of language. From within this “blessed invisibility,”⁵ I learned the generosity of silence and how to wait to speak until I was sure of my words. I’ve grown and been transformed by the generative nature of stillness and I’m drawn to others who inhabit this state—solitary, but not alone. With time, I’ve absorbed the pain of my calamity, yet the wound can always be located. It has become a wellspring for my work, and the process of making new forms is also a progression toward what I am, will always be, becoming.

Now, I make my way watching for signs that appear like spurts of cadmium yellow on the bark of a tree. It’s as though something waits for me to arrive at the metaphorical turn of the path in the forest, leading from one step, one moment, to the next. As a musician and DJ, I’m finely tuned to sounds, and find I’m sometimes able to hear something before it arrives.

The hope that someone will come looking for me may never go away, and yet I cherish my ghostly ways, free, safe and quiet, moving through what can’t be seen, praying for light. I wonder, was there ever a moment that was not like this?

How will history look back on the social expulsions of these times? I especially wonder about who among us, with time and distance, may be recognized as collateral damage in an otherwise righteous movement. I know some have not survived the experience. But what’s become of those who’ve continued on? How many are there, what story do they tell themselves? In what ways have they been changed? I like to believe there is a purpose, a collective wisdom percolating beneath the surface of what seems at times to be an unforgiving era. I confess an optimism that some number of those touched by the cancel experience, deserving or not, on one side and the other, are birthing new potential that will eventually infuse how we humans live together. That we can all learn from our mistakes.

Kalaupapa helped me understand my complicity. My fraught and sudden decision to leave a position running a media non-profit was the culmination of an ambitious agenda I’d set into motion when I’d taken the job more than a decade earlier. I’d been recruited to a leadership position, and, overcoming my fears, I accepted and found I loved it. I envisioned a new future for the organization and I learned to write and to speak publicly about things that were important to me, my colleagues, and to the wider industry. Over time and with many people, we manifested what became a new, collective vision for public media’s place in communities large and small, and we demonstrated the importance of independent, creative talent to the vitality of the industry. We accomplished a lot. It was exhilarating and exhausting. Years passed. Conditions changed, and so had I. I could still see the destination, but what once felt soaring became heavy boots on a steep climb. I sensed I was coming to the end of something.

With the pressures of success and without the guidance I needed, I lost sight of those working closest to me, those who needed me to respond to them beyond the boxes to be checked, or that plans for the next launch were in order. People responded in different ways to my insensitivity: disappointment, hurt, anger, or they left. Some sought retribution. The alienation from people I cared about, whom I deeply appreciated, took a toll on me, too. I needed to escape a work life that had become isolating and inhospitable, and remedy what had become a painful separation from myself. For more than a year before the end, there came to me an unbidden, ceaseless prayer: “help me, help me, help me.” And in an instant, I was out.

Today I’m drawn to the work of those who took themselves as far away as they could go, to be safe, be able to think, to work, to live, to begin again. They are legion.

Poet Robert Lax fled to Greece, rotating between the islands of Kalymnos, Kos, and, finally Patmos where, in a small room behind a blue door, he became friendly with himself. Out of this atmosphere and over the span of several decades, his poetic language emerged. “If you give it some time,” he said to filmmakers Nicolas Humbert and Werner Penzel, “writing is like dreaming. It will come naturally.” Thornton Wilder was 55 years old in 1962 when he left his home in Connecticut and drove west without a destination. His car broke down outside Douglas, AZ. He found a motel, rented a room, and stayed for nearly a year writing a book that, apparently, turned out pretty well. Five years later, the painter Agnes Martin headed west after enduring multiple stints in Bellevue (including electroshock therapy) and, finally, after being evicted from her studio loft on Coenties Slip in lower Manhattan. She took a bus to Detroit, bought a camper van, and drove aimlessly for two years until she arrived in Cuba, NM. She settled into a one-room adobe hut up a dusty off-road, across an arroyo, past barbed wire fences, rattlesnakes, rusted tin roofs and a scattering of soup cans pocked with buckshot. Martin would sit for hours or days in a chair put up against the wall next to her bed waiting for “an inspiration.” An image would take shape in her mind’s eye and, once its lines and colors were in focus, she’d pick up her brush and a straight edge, mix up her pigments, and get to work. Transposing the very small image from her inner vision onto a 6’ by 6’ canvas was, she said, her great challenge. Out of Martin’s chair-sitting came one monumental series of six paintings she titled “With My Back to the World,” commentary, it seems, for her ground of exodus. “It is necessary to be alone to visualize your work,” Martin said in a conversation with her documentarian Mary Lance, “To walk alone is very different than walking with others.”⁶ And what, then, becomes of those “others,” of the self, that’s been left behind?

Poet and scholar Fred Moten describes “doubling back” or recursive movement, as though there’s “an arm reaching into both new and old terrain.” He imagines a tree with a limb “wrapping around itself…by way of a kind of curve…(an) intense circle.” This movement is complicated, he says, “There's always this yearning, at the same time as there's always this reaching.”⁷ It seems to me this going around and around is a kind of waiting; to know when to move, how to speak, whether it’s time to mark your presence, as a gull etches circles in the sky, waiting to land, or perhaps just riding the current.

After seven years, a question of return came to me. I wasn’t expecting it. What would I go back to? The world and its troubles are the same. Why leave this new, ghostly way of being? What was behind me was gone, yet my confidence in what lay ahead now felt uncertain. I began to experience moments of disorientation, waiting for direction.

I once heard writer and poet Nathaniel Mackey tell a story about Elvin Jones trying to find a way out, not from exile, but being lost in the music. Jones was a jazz drummer known for extended solo breaks. ‘When I go on for so long,” said Jones, ”I’m looking for how to get out. Sometimes, the door would go right by and I don’t see it,” he said. “I have to wait until it comes around again. Sometimes it doesn’t come around for a long, long time.” And, of course, that door out is also the way in to something else.

I met a Quaker one Sunday morning in a meetinghouse thirty minutes outside Philadelphia. The room was small and perfectly square with long wooden benches that seemed as old as the stones that made up the walls. The plaque outside read 1720. John invited me to stay after the morning’s silent worship for “some shamanic drumming.” This was not the usual invitation at a Quaker meeting. I agreed to stick around and it turned out he, himself, was the drummer. I sat apart from another woman and a blind man on the old benches set into close, perpendicular rows. We shifted our bodies, doing our best to make a circle. John suggested we’d go on a journey, perhaps meet creatures who could help us. “Keep an eye out for the one you see three times,” he explained. “Go to them and ask for what you need, whatever questions are on your mind.” And we began. I closed my eyes, and my heart quickly matched his beat. I was in it.

I saw a portal across a lawn. A slice from the trunk of a fallen tree and been turned on its side, the center of it hollowed out to make a perfect “O.” I walked towards it, my body shrinking with each step until, when I arrived, I’d grown small enough to climb up onto it. I stood and saw through into a dense white cloud. A flush of fear passed through me. I pulled off my clothes and dove in. Now I was under water. I felt the pleasure of it on my skin and, again, the fear realizing I had no idea how wide this cloud-water passage was, or how far above the surface might be. My arms were strong and, with my one deep breath and a few strokes, I pulled myself across and up onto a bank of a wide and familiar pond. I found my footing and stepped carefully toward shore, watching a shoal of small fish skittle about my feet. A water snake wove out of its hiding place to make way. I reached the bank and began climbing straight up through the woods that circled the water, sometimes bending to all fours, brushing sticks and dirt out from between my toes. Soon, I reached the top and stood, scanning what was in front of me. I’d arrived at an open meadow and waited, taking in the sunlight wavering in the fullness of the day. Insects appeared as soft orbs, glowing and drifting above the wild grass. I watched ants moving about and then came the sound of a bee. It flew up beside me, and I recognized my imperiled bee from Kalaupapa. I greeted it, and knew I was where I was supposed to be.

I looked across the meadow and saw a large white horse standing quiet. I went across and reached for her, moving my hands across her back, inhaling her scent, caressing her jowl. Again, a flush of fear passed through me, and I wondered if she could sense it. Gripping her mane, I climbed onto her back, pressing myself to her. I squeezed my thighs against her flanks, and she carried me off to a third edge of the meadow. She stopped there. The woods in front of us were dense and dark. She waited for me to give her direction, but I felt there was no way forward. I was stuck. I despaired, recognizing this as my predicament of return. A voice from inside me said, “Turn around and go the other way.” It seemed the horse heard it, too. She turned quickly around and raced us both across to yet another edge of the meadow. I saw an opening. We rode through it to enter another clearing. I’d found my door.

__________

Author’s note:

For those seeking deeper understanding of Hawaiian culture, language, and history, I recommend Kipuka Database and The Hawaiian Electronic Library, and two oral-historical books by Pali J. Lee and John K. Willis that provide rich insight into pre-colonial life and culture of the native people across the islands:“Mo'olelo o na Po Makole, The Story of a Woman, a People, and an Island” (also titled “Tales from the Night Rainbow”) (1987) and “Ho’opono: A Night Rainbow Book” (1999)

Footnotes:

Translation: “two presents” or “double gifts,” Place Names of Hawaii; Mary Kawena Pukui, Samuel H. Elbert, and Esther T. Mookini.

The names of the first exiles: J. N. Loe, Kahauliko, Liilii, Puha, Kini, Lono, Waipio, Kainana, Kaaumoana, Nahuina, Lakapu, and Kepihe (taken from Hawaiian Legislature Bill SB679 HD establishing January as Kalaupapa Month).

Two Moral Essays: Draft for a Statement of Human Obligations and Human Personality (1943); Pendle Hill Publications, 1981.

“Heterologies: Discourse on the Other” (p. 115); Michel de Certeau; University of Minnesota Press; 1986.

“Tell Them I Said No” Martin Hebert; Sternberg Press, 2016.

With My Back to the World; New Deal Films (2003).

City Lights Bookstore presents Fred Moten and Nathaniel Mackey in conversion; June 9, 2021.

Photo by Mim Adkins

Sue Schardt is a conservatory trained musician, open water swimmer and once-professional cooker. She recently completed her first film, Nothing in the Way of Beauty, which is screening at community theaters and won accolades from numerous national and international festivals. Sue spends a good amount of time behind a mixing board stirring together a weekly radio show, In the Margin of the Other and, as DJ, was one of the artists whose work was exhibited at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art’s One Day at a Time: Manny Farber and Termite Art. Her extensive career in public broadcasting focused on innovation. Over decades, Sue’s work helped forge new paths to engage more people in communities large and small, and expand the industry’s vibrant network of independent talent. Her two guiding principles come from her clarinet teacher, Joe Allard, who said “to blow is not to play,” and Chef Laura Brennan, who advised her that “water is the magic ingredient.” You can contact Sue at sue@marginmedia.org.