Featured Poets: Fred Marchant and Yaryna Chornohuz

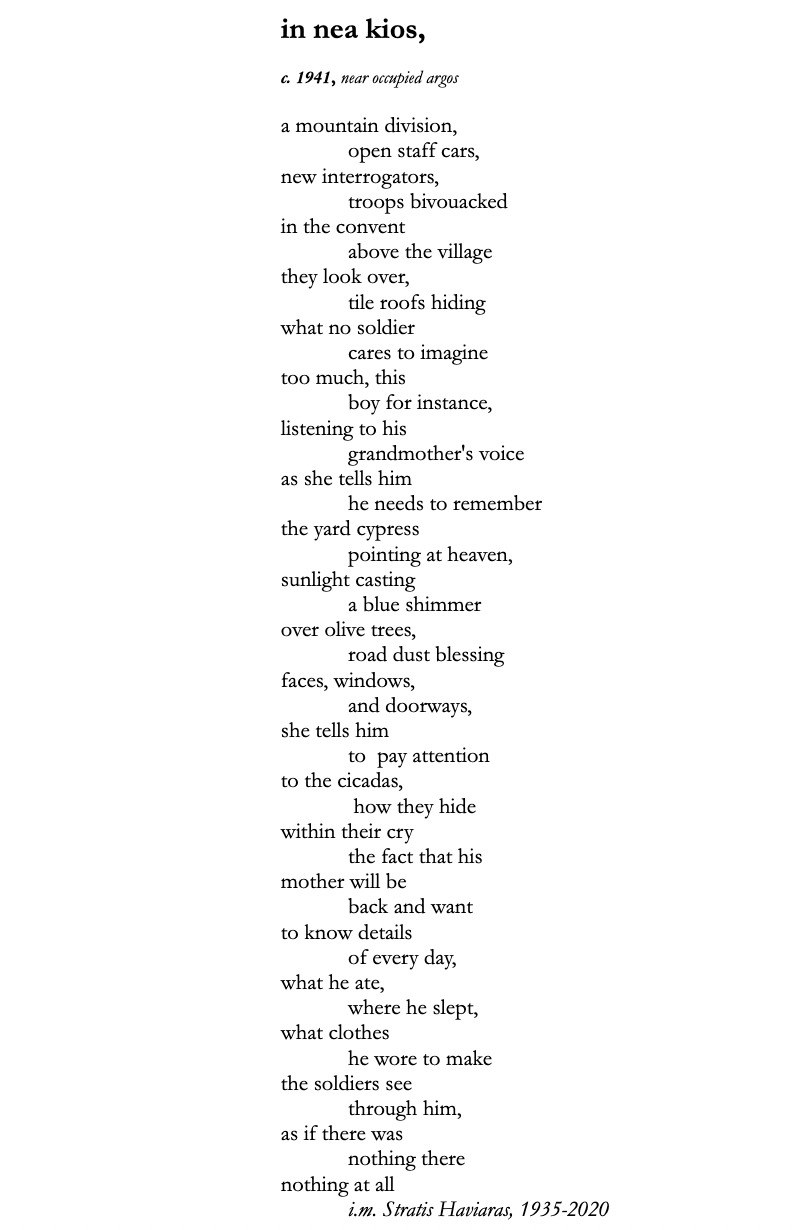

Fred Marchant

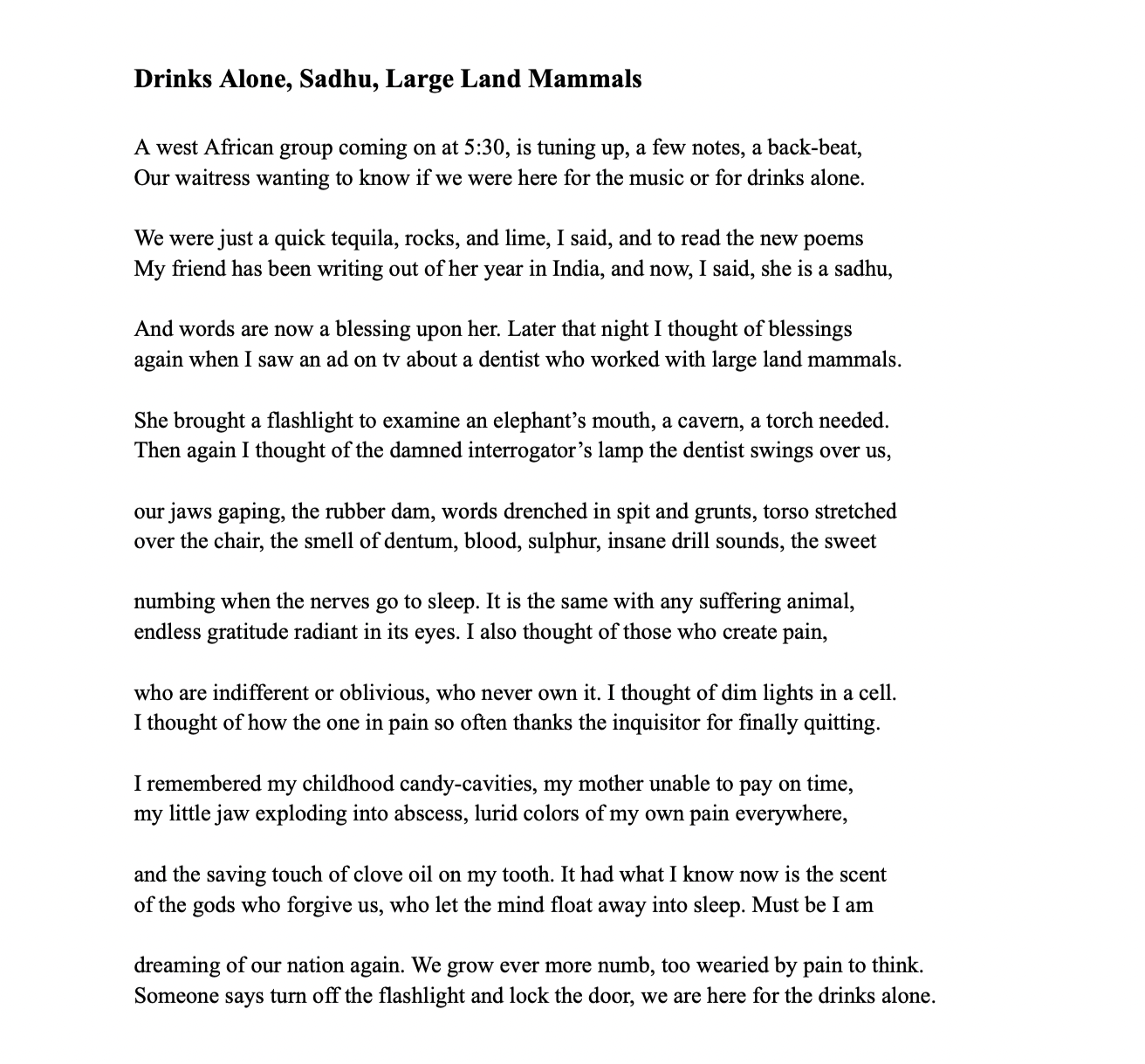

Among the many startling moments in this selection of Fred Marchant's poems, none is quite as surprising—and unsettling—as the monologue spoken by "El Alamain," Ronald Reagan's favorite horse. The noble beast's evaluation of his rider is unexpectedly affectionate:

I loved him because he understood

what I needed before

I did, which is the sign of a true leader, even if you

do not know it.

But it's when the horse begins to prophesize that we begin to grasp the poem's imaginative ambition:

But often in

the golden light I saw the shapes

of leaders I hated to imagine, the contempt

for us all in their eyes, the kind

who I knew would ride hard on everyone, break

out the whip for the likes of me,

use it even when they did not have to.

Fred Marchant has long been recognized by readers and other poets as one of our most important voices of conscience, heir to the legacy of poets such as William Stafford, Muriel Rukeyser and Daniel Berrigan. Like them, Marchant has earned this recognition not with his words alone but with the choices he has made in his life.

In 1970 Marchant became one of the first officers from the US Marine Corps to receive an honorable discharge as a Conscientious Objector, a stance he took to express his opposition to the Vietnam War. After earning his PhD from the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago, Marchant taught at Boston University and later at Suffolk University where he founded the Poetry Center. For years Marchant was a vital presence at the William Joiner Center for the Study of War and Social Consequences at the University of Massachusetts Boston where he participated in Creative Writing Workshops alongside Kevin Bowen, Grace Paley, Maxine Hong Kingston, Yusef Komunyakaa and many others. Working with Nguyen Ba Chung he has co-translated from the Vietnamese.

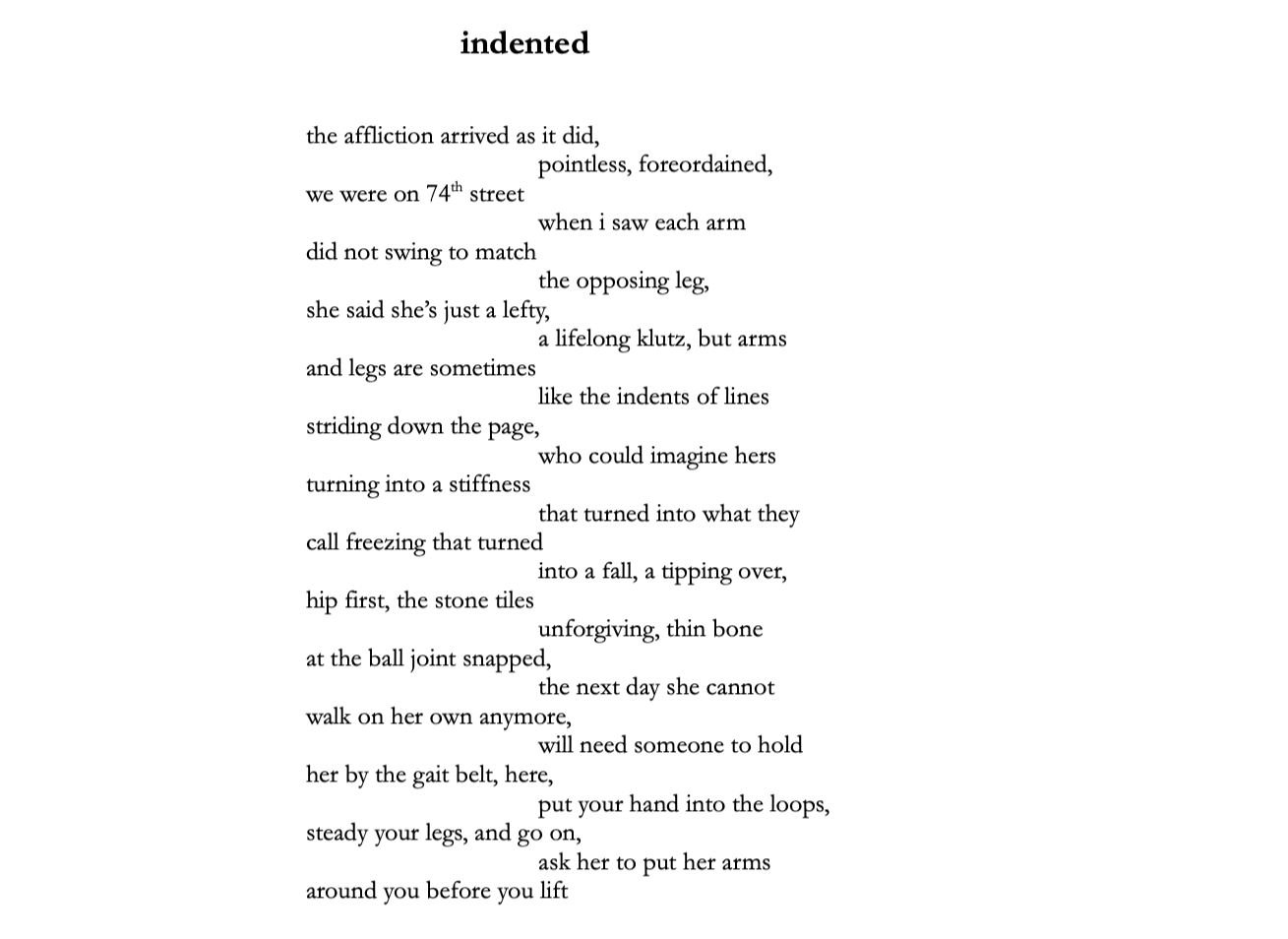

Marchant's work of witness continues to this day, as can be seen in "Detained," which takes place outside the ICE detention center in Burlington, Massachusetts. Never hectoring, his poems, quietly but firmly, register and take the measure of realities we would prefer to ignore: "We grow ever more numb, too wearied by pain to think." The pain, and the more personal sorrows alluded to here (including his wife's struggles with Parkinson's) are leavened by a visionary gleam. In a poem ostensibly about bird watching, he writes:

The bird you see is but one letter in an alphabet you need to learn.

Your lens is a sentence from a language that has no tenses.

Like the bird you watch, it hovers when it can, is entirely present.

Later, the bird so high you can hardly see it will fall asleep.

It sees you now but who can say what it sees when it does?

Who indeed?

— Askold Melnyczuk

Yaryna Chornohuz

“Greetings to you from my time,” writes Yaryna Chornohuz in a recent poem, “to those born after my death.” In a way, all of Chornohuz’s poems are messages in a bottle, cast out of Ukraine’s front-lines to a reader who may or may not have experienced war first-hand. She describes the tangible realities of the front-line – from VOG-grenades to the slag heaps of Donbas. Born in 1995 in Kyiv, Chornohuz – who is a senior corporal in the Ukrainian Armed Forces – has now spent close to a fifth of her life serving on the frontline. She first volunteered in 2019 and served as a medic. She would later join the Marines, and has recently retrained as a kamikaze drone pilot. Chornohuz’s first book, How the War Circle Bends, appeared in 2020. Her second book, [dasein: defense of presence] was published in 2023, and was awarded the country’s top prize for poetry – the Shevchenko prize. She recently published her third book of poems, Nobody’s Saffron (2025). Chornohuz’s poems include poignant descriptions of the human losses that come with war. But her verse is also about life, about her daughter, who lives in Kyiv, and whom Chornohuz gets to see during her periodic leaves, about her friends and fellow soldiers. They are poems about what is worth fighting for: the purple saffron on mountaintops, the freedom of visiting a filling station at night.

Translating Yaryna Chornohuz has meant attempting to bridge a gap between soldier-writer and distant reader. I’ve been lucky to work closely with two English-language presses—the UK-based Jantar has just published [dasein], and the Boston-based Arrowsmith. At Jantar, I had the benefit of working closely with two wonderful translation and poetry editors—Hugh Roberts and Fiona Benson. Arrowsmith will publish Nobody’s Saffron next year. I’m also lucky to have Yaryna at the other end of a text message, patiently attempting to answer my often foolish questions: what is a VOG? Can you tell me more about the gas stations at night? Who were you reading when you wrote this poem? Readers are not supposed to know the secrets that make a poem, but contemporary translators sometimes gain a patient, privileged view—if only for a moment.

— Amelia Glaser

[the game of transhumanism]

Greetings to you from my time,

to those born after my death,

from a time so

red, black, gray, white—

that in truth it can no longer describe itself

the meaning of my time hangs in the air,

a deep cello lingering

like morning in a forest

beyond the charred trees where war

usually walks

though now it’s howling ironically:

"war is walking by the window,

slumber lingers by the fence"

only the river sleeps,

she alone can sleep a sleep

that's not eternal.

Someday someone after us,

instead of us,

may sleep a non-eternal sleep—

may fall asleep on schedule.

Is it like this for you, too?

if only we could hear you...

have you seen the twisted faces

of our entrails as we, going off to war,

bid farewell to our loved ones?

If you see these faces in your time

borne out of a long war of attrition,

of annihilation –

remember, there are more like them

behind you.

don't hide your faces, don't fear them,

don't mistake this light—dim and piercing, almost-white,

streaming from survivors’ eyes,

for shiny, vile heroism,

someday no one will believe it,

but we were people, too.

Someone will say, solemn and reproachful,

"she aestheticized the war

with her poems,"

not knowing that really, dear comrades-brothers-sisters,

when I wasn't standing watch, —

I wept like a fool

so many times it was embarrassing,

I felt bitter, unaesthetic,

I didn't feel like fighting to survive,

I even hoped I’d die fast

like the others.

When I finished writing this letter,

the next air-alert—indifferent to all—sounded.

The children in their schools indifferently ran into shelters

decorated with painted flowers.

And the siren, joining the cello, was

like just another wind instrument.

If you only knew

just how good,

how hatefully good

it sounds.

Translated, from the Ukrainian, by Amelia Glaser

(from Nobody’s Saffron)

[saffron]

Saffron always grows

on dry grass,

on the passes between the mountains' teeth.

You'll find its crocuses amid the dryness—

its purple blossom a painful privilege of survivors.

I can lie in the saffron for hours.

Its color nips at my soul.

Meanwhile someone else

gnaws into my heart, as if into the earth,

plowing a red trench

to defend themselves from the enemy—

the enemy has become life itself.

I walk barefoot on a mountaintop

among the purple saffron, hoping

a snake will bite me

as it once bit

Prince Oleh

in the Kyiv hills.

I hide from the world in the saffron,

as if from the enemy in a trench.

And the spring bloom that flowers in May—

this worn out symbol of beauty—

this is what the dead won't see,

this is what we will see in their place...

It is cold in the sun.

It is dead in the world.

The saffron, which always grows in the mountains in April,

just is.

Translated, from the Ukrainian, by Amelia Glaser

(from Nobody’s Saffron)

[naked baroque]

once upon a time, as it is now, the world was a stage for artists

where in any scene an unknown soldier might fall,

and obviously, making their exit, someone would smash a wine glass

at someone else’s feet

the naked baroque

just showed up like this, like something unforgivable,

and everyone assumed it belonged to them

its bare body was marked

with a black-red target

and friction burns

the force of friction is the first thing a soldier must learn

before a neverending dawn—

the endless pressure of the surfaces of earth the surfaces of bodies

gives birth to vision, as if with every layer of clothing

you take off, you put on

a second skin

the naked baroque left rolls of fleur-de-lis wallpaper propped in the corner,

a white-emerald cathedral

the pinkness of dark, uneasy crannies,

furniture, dishes, paintings

frenzy, boredom, frailty

stiff hands and hushed words

it left

a cold potholed floor

tension that's left its colour

on the nakedness, like on the last snow in March

it set up a mirror

where everyone who goes there and isn't asleep

must look at themselves

at first the naked baroque broke down the walls, then it went out

to the woods

and started digging up the forest's heart

which, even after the world has turned a thousand times, proclaims

this truth to whoever digs it up—

here in this place

so much tension, so much pain, so much loss,

so much death, so many flowers, so much wood,

so much carving

only a naked marble slab

can hold it all

and absurdly the finest inlay is kept for the hidden places

where language alone carves blocks

into pillars

no one will forgive us the naked baroque

God speaks in deaths, receives answers in iron

grants forgiveness in love

that orbits the Sun together with our planet

soundless to the point of deafness

hi there, my vanishing

hi, answers love

you hear how you disappear in the cyberhaze beneath the beating

of the forest heart…

naked baroque

no one will forgive us for you

Translated, from the Ukrainian, by Amelia Glaser

with Fiona Benson and Hugh Roberts

(from [dasein: defence of presence])

[gas stations]

Intellectuals know—when war comes

and occupation,

the first thing to get looted

in our civilization

is the mini-mart at the gas station

when I travel this country's roads in the dark

between horizon and moon

I'm sure to stop at a gas station

dressed in the clothes of the one I’ve lost

his red T-shirt

and black hoodie with an aquamarine aeroplane

he wore off-duty

long, frayed thermal, holes

at the right elbow

green fleece bag inscribed with his callsign

these clothes are lonely, even on me

but after a while, like pressure building in a tiny boiler,

I’m compelled to put them on again.

On my monthly trip to the gas station

I begin to live

a little more than usual

along with the one I’ve lost

as though you were a little fleck of prose

in an imperfect poem

non-being tosses itself sweetly into the expanse

like a piece of candy

there are clothes you're more afraid to lose than your life

—green lights across all Ukraine

and the body is tucked out of sight

down black-mouthed roads

like the asymmetrical corners of sheets

in army barracks

intellectuals know this, too, among other things:

in this country there's a bureau of letting go

of lost people and property

I love Ukraine's gas stations for their freedom

at the end of each month at this old gas station with no mini-mart

I die along with the one I’ve lost

this is absolutely permitted

it’s your inalienable right

enforced by law

and by the enemy

Translated, from the Ukrainian, by Amelia Glaser

with Fiona Benson and Hugh Roberts

(from [dasein: defence of presence])

Yaryna Chornohuz is the author of three collections of poetry, as well as a senior corporal in the Armed Forces of Ukraine. She enlisted in the Ukrainian military in 2019 and served as a soldier and medic in the 140th Marine Reconnaissance Battalion. She was awarded a Medal for Lifesaving in 2022. She is a winner of the Shevchenko Prize for poetry (2024). She has been included in Focus magazine’s list of 100 most influential women in Ukraine. She has traveled to the US to testify before Congress on the need for funding Ukraine’s military defense. She has been profiled in the New Yorker and the New York Times for her poetry, activism, and military service. Before joining the Armed Forces, Chornohuz studied philology at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy.

Amelia Glaser is a Professor of Literature at UC San Diego. She is the author of Jews and Ukrainians in Russia’s Literary Borderlands (2012) and Songs in Dark Times: Yiddish Poetry of Struggle from Scottsboro to Palestine (2020). She is the editor of Stories of Khmelytsky: Competing Literary Legacies of the 1648 Ukrainian Cossack Uprising (2015) and, with Steven Lee, Comintern Aesthetics (2020). Her translations, from Ukrainian, Russian, and Yiddish, include Halyna Kruk’s A Crash Course in Molotov Cocktails, co-translated with Yuliya Ilchuk (Arrowsmith, 2023). She is currently writing a book about contemporary Ukrainian poetry.

Fred Marchant is the author of five books of poetry, the most recent of which is Said Not Said, published by Graywolf Press and designated an Honored Book by the Massachusetts Book Awards. His earlier collections include Full Moon Boat, The Looking House, and Tipping Point, winner of the 1993 Washington Prize from The Word Works. Marchant is also the editor of Another World Instead, a selection of early poems by William Stafford, and is a co-editor with Jennifer Barber and Jessica Greenbaum of Tree Lines, an anthology of contemporary American poems about trees and forests. His own poetry can be found in numerous anthologies, most recently in Braving the Body, a collection of poems about illness. Marchant has also published poems and reviews in a wide variety of literary journals, including AGNI, The New Yorker, Solstice, and Plume. In addition, he has co-translated (with Nguyen Ba Chung) the work of several contemporary Vietnamese poets. He is an Emeritus Professor of English at Suffolk University in Boston, where he founded the Creative Writing Program and Poetry Center. He lives in Arlington, MA.

Askold Melnyczuk has published five books of fiction. His first novel, What Is Told, was the first commercially published novel in English to bring to light the Ukrainian refugee experience and was named a New York Times Notable. He guest edited a special issue of Irish Pages on The War in Europe, available here. His first collection of poetry, The Venus of Odesa, will be out from Mad Hat in the spring of 2025. A selection of essays and reviews, The Dangerous Tongue: Why Literature Matters More Than Ever, will be out from the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute in 2026.