Featured Poets: Vasyl Makhno and Christianne Goodwin

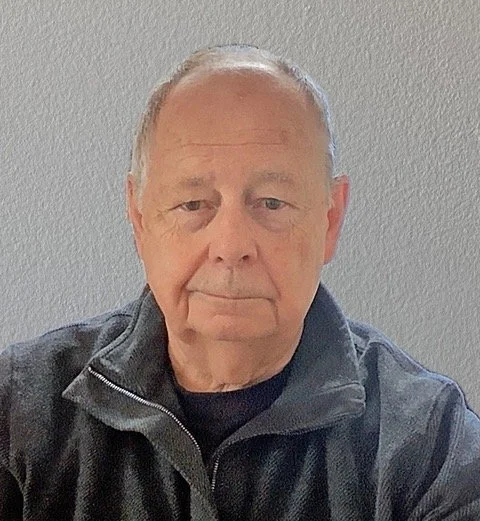

Vasyl Makhno

After fleeing Hitler's Germany in 1934, the philosopher Theodor Adorno despaired: "Every intellectual in migration is, without exception, mutilated....He lives in an environment that must remain incomprehensible to him." After a century, or more, of near-constant cross-cultural pollination, fueled by incessant political and social instability, which has seen so-called dissident intellectuals from countless countries survive the struggles of repatriation, a new attitude to the displaced mind has evolved, offering an alternative to Adorno's bleak and bitter assessment.

Vasyl Makhno, a Ukrainian writer widely recognized as one of the leading voices of his generation, is neither an exile nor an immigrant exactly. Makhno has carved his own path. Born and educated in Ukraine, he has lived in the US for a quarter of century while continuing to write in Ukrainian. After publishing his doctoral dissertation about the poet Ihor Bohdan-Antonych at the age of 25, he taught for a time in Krakow before moving to New York where he has been since 2000. Makhno's work is marked by an absence of nostalgia—the usual tonal tropes of exile and loss have shaded into a mature acceptance. The poems are, as the writer Oksana Lutsyshyna put it, "liberated from the discourse of liberation." This does not mean they are without feeling, but that the speaker in his poems appears to be at peace with his condition.

The sequence from which the following three poems are excerpted, is titled "Towards Homeland." Instead of conjuring a mood of longing and sorrow, bereft of the definite article ("the homeland" would be the more typical locution), the noun instead evokes something more akin to Graceland. The final poem here ends with the speaker, whose meditation on the Atlantic shoreline has been disrupted by the arrival of some rambunctious children, sighing:

I was angry

with them and their careless parents,

as if I had no other worries

but other people's children?

As if there were no homeland, only a direction?

Translated from the Ukrainian by Jaroslaw Anders.

About a Crow

Mom returned from a trip and says:

“I barely opened the gate. But the house key

was in its place – it’s just more rusted.

And how about you?” She went to look

at our family cottage, which has been empty

for about two decades.

“Here,” I say, “the ocean has changed its color, and

I’m translating Carver.” Mom replies

that she has never seen the ocean and never heard of Carver.

“The ocean,” I say, “cannot be seized by the eye,

and Carver is an American prose writer and poet.”

“Don’t make things up,” says mom, “you’re always making things up.”

I imagine she didn’t go through Chortkiv,

but through Buchach - a nicer road, less damaged

by trucks. Then she approached the gate.

No, first, she must have taken her cane,

because she managed to say the acacia seeds,

that float in from the other side of the road

were sprouting around the barn. "They reach," she says,

“up to my waist." “What about the fence?” I ask.

“Yes,” she says, “everything’s collapsed and there’s no one

to talk to: those who are at the front are at the front,

and those who aren’t are hiding. You understand,

the war.” “I understand,” I say, “the war.”

“But everything else is in place?” I ask my mother.

“Where would it go? And Horb-Dolyna,

and Ta Hora, and the Dzhuryn, and everything that was

ours is in place, don’t you worry. And the lid

of the sky, and the Dzhuryn’s weeping, and the smell

of burning potato stalks, and the war.” And my mother sighs.

“If you want, I’ll read you my translation,” I say.

“Is it long?” “No,” I say, “It’s short. It’s called ‘My Crow.’”

“About a crow?” “Yes,” I say. “About a crow.” “About an ordinary crow?”

“Why are you surprised?” “Because when I was walking along

the wood, in front of the road sign, crows

were walking on the road and picking up grain.”

A day later I talk to my childhood friend.

"I'm going,” he says, " to prune the acacias."

Like my mother, he rarely visits his family places.

He probably remembers the sound of the Dzhuryn

the wormwood smell of clay pits, swallows before the rain,

our childhood rambles, our swims in the river.

What's the point then of visiting often

if you carry everything in your memory like a matchbox,

just in case? "Half of the houses," he says, "are empty.

The smithy has collapsed. The old clubhouse has collapsed.

And how about you?" he asks. " I’ve translated a poem by Carver."

"What poem?" "About a crow." "About an ordinary crow?"

he wonders. “Yes,” I reply. “Don’t crows have a place in poetry?”

“In those acacias,” he admits, “there are so many crows’ nests.”

I imagine how he’ll be cutting the gnarled branches

with a saw. How the crows’ nests will fall to the ground,

how he’ll pull them to the shed, for they’re good for kindling,

and in the spring, the crows will weave their nests again,

but not in the acacias. Smart fellows will find other trees.

Females will lay eggs in the nests,

elongated eggs, as if smeared in clay,

and in the summer, they’ll fly in flocks along

the horizon towards Pozhezhe. “Maybe it’s because of the war,”

mother said after hearing the translation,

“that there’re so many crows in our sky?”

A Nut Tree as a Deer

Geese flew over the roofs. And from the ocean

a helicopter rumbled. Snow clouds were gathering,

the wind was howling. I pulled out a shovel and leaned

on the handle, looking for another goose flock,

which I didn’t see. I heard it, though.

Perhaps the nut tree saw it, because it's tall.

Letters collected in the computer

I haven't replied to for a week, so back home,

I breathed on my frozen fingers

and read bold subject lines.

I forgot to ask the nut tree about the geese:

where did they go? It certainly saw them.

But maybe it won't tell me, because who am I to it?

In the summer I sit in its dappled shade.

In the fall I complain about the red tiles of its leaves.

In the winter, what about the winter? Well, I ask it about geese,

about the brooding sound of the ocean, and its silent

coexistence with the house.

The nut tree often peeks into my window on the second

floor and even leans down to the cellar windows.

From its trunk, two thick boughs spread

in opposite directions like the antlers of a deer.

I tell it that it is a deer because its antlers

sweep away hanging snow clouds like a rake.

“I am a nut tree,” it replies, “what a silly comparison.”

It will stay offended until the next morning

when the snow settles on its branches

and makes it as white as my head.

It will be proud of this sheepskin coat:

“To wear such a sheepskin coat –

it will say, “one must stand all night in the snow,

and you couldn’t do it.” I’ll hear its boasting,

as I clean the snow again and

shiver a little, but the tree will be in a sheepskin,

and I only in a coat, quite worn out in fact.

“This is how life passes,” I will think, “together with

the winter.” “Why so blue?” the nut tree will ask,

take my sheepskin,” and with its whole deer body

it will shake on me a thick blanket of snow.

It will shake it down – and seal my eyes and mouth,

it will shift its burden onto my shoulders,

it will cover the path I’ve just walked.

My waterproof sneakers are getting wet,

my Bologna jacket and knitted gloves are getting wet,

my lips are getting dry. I pick up the shovel again,

and again move the snow feeling

some right behind my collar. And the nut tree

has already turned into an orchestra, for the ocean winds,

catching on its branches – the deer antlers –

play both the zither and the bandura.

“Write your letters,” I hear from behind, “the snow

will be falling all night. Don’t struggle, you won’t win.

And the geese you were looking for are still flying,

one can hear the limbar swish of their wings, trust me.”

“I can’t hear it,” I say. “Perhaps you can’t, but they

are still flying. Come closer and you’ll hear them.”

I put down the shovel and walked to the trunk –

I stroked it like a deer. A long winter ahead –

we’ll have many arguments

with the nut tree. But why this problem

with being

a deer?

Towards Homeland

I went down to the ocean, everything’s as usual:

cormorants and martins on the stilts,

the tide – so-so, but windy.

On the wet sand – thousands of footprints.

They walk and walk, despite the bitter wind,

but they wrap themselves in jackets and hoods.

I took a picture on my phone, sat on the trunk

of a fallen tree. I thought about a poem:

“I’ll probably start a line with martins

when I return home” – and I forgot about it,

because I was gazing at the white speck of a yacht

dissolving in the blue next to a dark tanker.

Then I heard a single-engine plane.

It rumbled, choking, overhead.

The martins, used to my presence,

soared from the stilts and alighted on the shore.

They must have expected to be fed,

but there was nothing in my pockets

apart from my phone and a paper clip

stuck in the seam. If I only could find something:

guiltily, I stood in front of them,

spreading my arms. Suddenly, on the sandy

path overgrown with all sorts of bushes,

five adults with three children appeared.

The children rushed towards the martins which flew

back to the piles. The adults sat down

on the sand, the children stripped to their T-shirts.

“Hardened,” I thought, “or parents don’t care?”

The children were running along the shore. I snuggled in my jacket.

Where the yacht had vanished in the mist behind the tanker

was my homeland, or rather the direction towards it.

The wind was picking up. The sleeves of children’s

t-shirts flapped. The tanker was getting nearer.

Yes, yes, I often come here

to stand by the ocean and look towards

the homeland. Now the children were shouting,

kicking me out of my first line

of thoughts about homeland. I was angry

with them and their careless parents,

as if I had no other worries

but other people's children?

As if there were no homeland, only a direction?

Christianne Goodwin

While grounded in the Anglophone world, Christianne Goodwin’s poetry engenders a project on a global scale. In these poems the speaker takes us to imagined upstate New York, England, Russia, Budapest, and beyond to the surreal world of playing “Jeopardy! with Anne Carson.” Goodwin’s poetry commits to the rare balancing act of pairing lyrical turns with narrative constructions. In the poem, “Rabbit-Crossing Country” the speaker explores the name Pushkin by breaking down the word into sonic parts, forming semantic puzzle pieces out of the name, each worthy of their own investigation. The 24-line poem sings in a variety of cadences from playful curiosity (“Or mayhaps ushkin is a fantastical name / for a rabbit creature, much like the one / which crossed Pushkin’s path) to a more formal elegance (the ush with a u like usually / calls to mind the sound of win / or breath, pushing me further / in, but I cannot ignore kin.”) “The Isle of Dogs” is a brief love lyric, while “Jeopardy! with Anne Carson” is a short humorous one: both are marked by a clever intensity that feels effortless. On the page, Goodwin’s poems show a range of forms with time-tested structures of the tercet and couplet, well suited for the modern day mini/mock Odyssey in “Through Upstate.” Or in “Budapest (Fragment),” the words appear in a hallucinatory sort of free verse, hovering across the page like a cloud in a painting.

James Fraser

Rabbit-Crossing Country

After Zaffar Kunial

There’s something hidden in the name

Pushkin—in the middle, or on the sides

of the middle as I whittle my way through

(and once I’ve gotten past the thought

of an overlarge cat)

the ush with a u like usually

calls to mind the sound of wind

or breath, pushing me further

in, but I cannot ignore kin

and its obvious connotations

winding me back to ush

a sound of surprise, or slight pain

or perhaps the wind knocked out of you

Or mayhaps ushkin is a fantastical name

for a rabbit creature, much like the one

which crossed Pushkin’s path

on the way to Saint Petersburg (Peter Rabbit

was likely an ushkin after all)

The rabbit crossed on the eve of an uprising (push, in)

it’s lucky the poet didn’t,

though his kinsmen were there

After the rabbit, the driver’s mush

turned them round into the hush

un-riotous quiet

The Isle of Dogs

Birds in the short garden palms,

mudlarkers to my left,

you, home, while I venture out

to ASDA, through Mudchute,

by sheep and cityscape

We won't live here long.

We'll be taken away, from here,

from one another, then find

ourselves again, each other

And when I think of the color

of the sky that solitary evening,

I might just get carried away

and add back the "u"

Budapest (Fragment)

The storm came back

to scatter these lines:

sill with smoking wrist

thin filters semi Surrealists

murmurs of Kant or Kundera

dawn in two triangles

Is it tension or release?

A storm with Beat tendencies

tugs at my sensibilities

Now, through the gaps,

falls the rain

Jeopardy! with Anne Carson

Watch where you step!

Someone’s come and cut

gaping holes in the set

Circling one, I say

“What is wrong?”

and I’m correct

Through Upstate

A week ago, this

would have been ablaze

Now, stripped to the last reds,

we drive through Upstate,

me, sleeping most of the way.

It’s a shame I slept through it.

I missed those covered bridges and rivers,

missed a whole valley of residual color

and something else, I’m sure

(note the space in this stanza)

Won’t you tell me about it?

The stretch since Ithaca

That space, you see,

it’s just for you

Vasyl Makhno is a Ukrainian poet, prose writer, essayist, and translator. He is the author of fourteen poetry collections, including Skhyma (1993), Caesar’s Solitude (1994), The Book of Hills and Hours (1996), The Flipper of the Fish (2002), 38 Poems about New York and Some Other Things (2004), Cornelia Street Café: New and Selected Poems (2007), Winter Letters (2011), I Want to Be Jazz and Rock’n’Roll (2013), Bike (2015), Jerusalem Poems (2016), Paper Bridge (2017), A Poet, the Ocean and Fish (2019), and One Sail House (2021).

He is also the author of the short story collection The House in Baiting Hollow (2015), the novel The Eternal Calendar (2019), and five books of essays: The Gertrude Stein Memorial Cultural and Recreation Park (2006), Horn of Plenty (2011), Suburbs and Borderland (2019), Biking along the Ocean (2020), and From Consonants to Vowels: An Encyclopedia of Names, Places, Birds, Plants, and Other Things (2023).

In 2024, the Lviv-based Stary Lev Publishing House released Makhno’s selected works in two volumes: Skhyma (Vol. 1: Poems) and Chickens Don’t Fly (Vol. 2: Essays).

Makhno’s works have been widely translated into numerous languages, and his books have been published in Germany, Israel, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Serbia, and the United States. He has participated in international literary festivals in Germany, Poland, Nicaragua, Mongolia, Serbia, Turkey, and other countries.

He has translated poetry by Zbigniew Herbert, Janusz Szuber, Bohdan Zadura, and Anna Frajlich from Polish into Ukrainian. His honors include the Serbia’s International Povelje Morave Prize for Poetry (2013), the BBC Book of the Year Award (2015), and the International Ukrainian-Jewish Literary Prize Encounter (2020), among others.

He currently lives in New York.

Jaroslaw Anders is a Polish-born literary translator and critic specializing in East and East-Central literatures. He is the author of Between Fire and Sleep: Essays on Modern Polish Poetry and Prose (Yale, 2009). His essays and reviews appeared in the New York Review of Books, The New Republic, Los Angeles Times, and Liberties, as well as in several Polish periodicals. His translation of Vasyl Makhno’s collection of short stories The House in Baiting Hollow is forthcoming this year from the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute (HURI).

Christianne Goodwin is a poet from Michigan. Oracle Smoke Machine, her art-and-poetry collaboration with painter Stephen Proski, is out with Staircase Books (Cambridge, MA, 2023). Her work is published in Consequence, Peripheries, and Poetry Ireland Review, among others; Hungarian translations by Beata Princes are published with SzifOnline and Italian translations by Stefano Bottero have appeared in Nuovi Argomenti. She is a poetry reader for The Midwest Review, the recipient of an Academy of American Poets University Prize, and a Robert Pinsky Global Fellow.

James Fraser lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He manages the Grolier Poetry Book Shop. With his wife Bella Bennett, he co-founded the small press Staircase Books.